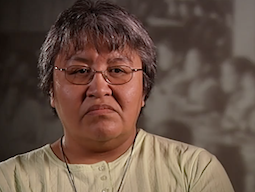

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

L'INTERVIEWEUR: Pourriez-vous s'il vous plaît dire et épeler votre nom complet pour nous.

LORNA ROPE: Je m'appelle Lorna Rope. Et tu veux que je l'épelle?

Q. Oui, pour nous assurer que nous avons parfaitement raison.

A. Corde Lorna. Mon nom de famille est Rope.

Q. Merci beaucoup.

Et où habitez-vous?

R. J'habite à Regina.

Q. D'accord. Est-ce de là que vous êtes originaire?

A. No. I’m originally from the Carry The Kettle First Nations.

Q. Dans quelle école êtes-vous allé?

A. I went to the one in Lebret. At that time it was called St. Paul’s, I believe.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous quand vous y êtes allé?

A. I believe I went there in the Fall of ’62. But there are some discrepancies around that because they are saying I went there in ’63.

Q. D'accord. Combien de temps êtes-vous parti?

A. Neuf ans.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous y êtes allé?

R. Je crois que j'avais 5 ans lorsque j'ai commencé et j'ai eu 6 ans lorsque j'y étais. J'avais 6 ans en octobre et j'ai commencé en septembre.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous de votre premier jour d'école?

A. I remember my first entrance, my first day into the school, into the whole building itself. I don’t specifically remember the first day of school. But I remember this massive red brick building and my mother was taking me in, my mother and dad were taking me in.

They took me to the Play Room, down on the main floor. They just kind of said goodbye to me and kissing me. My mom was crying and I didn’t know why. I didn’t see her after for quite a while.

Q. You didn’t know that you were going to be left there?

A. No. That was the hardest part because I didn’t know why I was there and why my mom and dad would leave me in such a place. I didn’t know anybody. The Nuns weren’t very helpful. They would just tell me to shut up and be quiet. I couldn’t do anything about it. I just sat there and cried.

Q. À quoi ressemblait une journée typique pour vous à l'école?

A. It was getting up really early. I believe we got up around 6:30, or something, and we used to go to church just about every morning at the beginning. Then at 7 o’clock or 7:30 we had to go for breakfast. And then after breakfast there were our chores to be done. After the chores were done we would have a few minutes to relax, or whatever, play around and take our minds off what was going on. Then we would all line up for school and we would all march down the hallways.

We weren’t allowed to look at the boys, even as little girls. We had the Nuns beside us marching us down the hallways, I remember, and if we looked at the boys crossing they would hit us on the head with their knuckles and tell us we were pagans. They would tell me I was a pagan, I would go to hell because I looked at this boy, and different things like that.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous du genre de tâches que vous deviez faire?

R. Nous avons dû balayer la salle de jeux et nous avons dû dépoussiérer. Nous avons essuyé les casiers, nous avons tout essuyé et lavé les planchers.

Q. À quoi ressemblait la vie avant d'aller au pensionnat?

A. Before I went to Residential School I was a happy kid, I believe. My parents looked after me. There wasn’t too much alcohol involvement yet. My dad was a hunter. I always remember we always ate wild food. I didn’t know what beef or chicken was, or really anything, because my dad was always hunting rabbits and deer and ducks, you know, the wild game in our area.

Q. Vos parents étaient-ils allés au pensionnat?

R. Oui, ils l'ont fait. Mon père est allé à Lebret et ma mère à Brandon.

Q. Vous en ont-ils jamais parlé?

A. My mom talked about it a little bit. My dad never really mentioned it. He would just say that he went. He didn’t tell me much about his experiences there. But from the way he treated us at different times, he was abusive at times, when he would get angry he would kind of lose control and he would hit us on the head with his knuckles, and that was the same way the Nuns did to us, to me, when I was there. I remember them doing that. As I got older I correlated the two and realized that my dad had picked this training up from the school and realized it wasn’t part of himself. But yeah, he was abusive from the Residential School.

My mother was more caring, more kind. She was more loving. I don’t know where she picked that up from, but she did. She was like that with us, I remember. Me being the oldest one, I remember a lot about my mother because she would hug me and tell me she loved me. It was a rare occasion my dad would ever do that.

Q. Vous les aimez?

A. Oh oui. Je aime mes parents. Mes parents sont tous les deux décédés, mais il ne fait aucun doute que je les respecte et les honore toujours. Ils ont vécu beaucoup de choses en ce qui concerne les pensionnats indiens et ce que cela leur a fait émotionnellement et mentalement.

Donc, vers la fin, à mesure que de plus en plus d'enfants arrivaient, il y avait plus de consommation d'alcool et chacun d'eux a suivi en séquence jusqu'au pensionnat. Étant le plus âgé, j'y étais le plus longtemps. Mon seul frère admet toujours qu'il était là plus longtemps que moi parce qu'il n'arrêtait pas de tomber dans ses notes! Mais c'était lui.

Q. Comment l'expérience des pensionnats indiens vous a-t-elle touché?

R. Cela m'a vraiment affecté de nombreuses façons négatives. Mais cela m'a également aidé avec beaucoup d'autres compétences en leadership que j'ai appris à porter avec moi jusqu'à un moment de ma vie.

Being at school when I was younger I was always told what to do. I didn’t have a mind of my own. I was belittled. I was called a savage. I was told I would never amount to anything. I was just a dirty ol’ Indian. I was just a dirty Indian and I wasn’t going anywhere in life. When you’re told that long enough you come to believe that you’re nobody and I felt like a nobody.

Being in the school I had a cousin who was really fair and she had freckles and she could fit more into the White society than us. But we always had this kind of game or contest we would play with one another. We all wanted to be White. We wanted to be like my cousin. So sometimes we would wash and wash ourselves so we would think we were White and we would go to her and compare our skin. At the time we just thought this was something we did. But now that I’m older I realize that I was trying to —

Je perdais mon identité.

— Speaker overcome with emotion

C'était un endroit isolé. Beaucoup d'enfants, mais seuls. Je me souviens d'être assis dans le dortoir. Je connaissais la direction de la maison. Je savais dans quelle direction je venais à l'école. J'ai toujours souhaité que chaque voiture qui descende cette colline soit ma mère et mon père pour m'emmener loin de cet endroit.

— Speaker overcome with emotion

But unfortunately I didn’t see my parents that often. After more and more of my siblings came, they came less often.

But I learned how to appease, I guess, the Nuns so that I wasn’t abused so much. I learned how to defend myself.

Q. Comment l'avez-vous fait?

A. I remember when I think I was in about Grade 1 or 2, this one other girl in the Play Room was a little bit larger than myself and she was more aggressive. Why she picked on me, I couldn’t tell you why or what the purpose was for that or the meaning behind it. Only she knows. But she would always fight me all the time. It was like the Nun wouldn’t do anything.

Donc, ce jour-là, j'en ai finalement assez de ses abus et de son intimidation. Je balayais le sol avec un de ces longs balais. Ils sont assez lourds. J'ai réussi avec ma colère et ma rage à ramasser ce balai et je l'ai frappée à la tête en légitime défense. J'étais fatigué d'être maltraité. Après cela, elle m'a laissé seul, voilà.

Donc à ce sujet, cela m'a montré que si j'étais agressif, les filles me laisseraient tranquille ou essayeraient de me déranger. Alors j'ai en quelque sorte maintenu cette idée quand j'étais enfant: être plus agressif et ne pas laisser les gens me pousser.

Q. Est-ce que cela a continué dans votre vie d'adulte?

A. Ouais. Malheureusement, cela s'est produit jusqu'à mes vingt-cinq ans. Jusqu'à vingt-cinq, j'avais un style de vie très tumultueux.

In regards to a lot of my teachings in Residential School, I wouldn’t listen. I came to a place where I became rebellious at the Residential School, because as I got older I started realizing I could think for myself. I don’t need anybody to tell me what to do, what time I can go to school, what time I can go to bed. I can do this any time I want. I was starting to be a pretty tall girl and I was pretty active, so I wasn’t a couch potato or anything like that. I was kind of like a leader also in the games. I played basketball, baseball and volleyball.

D'une manière ou d'une autre, j'ai réussi à me frayer un chemin pour devenir capitaine de ces équipes. L'une des raisons pour lesquelles je voulais faire partie des équipes était que nous allions pouvoir quitter l'école. Nous allions aller à différents endroits. Parce que mes parents ne sont jamais venus pour moi, je n'ai jamais eu l'occasion d'aller nulle part. Donc, cela m'a donné une certaine liberté de l'école.

Mais cela m'a aussi donné une certaine estime de moi, que je peux le faire. Être capitaine était vraiment quelque chose dans la journée. Donc j'ai en quelque sorte gardé ça derrière ma tête. Une partie de ce qui m'a aidé à l'école était que j'aimais jouer de la musique. J'ai appris à jouer de la musique, je pense, quand j'étais en 5e année. J'ai joué de la musique. J'ai joué de la clarinette. Ensuite, j'ai joué du saxophone, des instruments de musique un peu plus difficiles à gérer, mais j'ai pu le faire et j'ai apprécié ça. Ce sont quelques années que j'ai vraiment aimées.

The music teacher, we all liked him. He was such a nice man. For me he seemed to be a nice man because it seemed like he cared about us, about me. Nothing sexual or anything like that —

C'était plutôt un type paternel. La musique qu'il nous a donnée était vraiment bonne pour moi à l'époque.

But as I got older and I went back to school, into Grade 9, at that time I didn’t want to be there. I wanted to be at home. I wanted to be with my parents. Yeah, I gave them a difficult time and I realized I wasn’t going to be told to do anything any more. I wanted to do it myself, do it my way, let me try it myself, my way, you know.

So eventually they got tired of my rebellion and they told me I can go home. (Laughter) They just couldn’t do anything with me. If I decided I was going to go downstairs in the middle of a classroom session and watch TV, I just did. And if the supervisor came down and shut it off, I just got up and walked outside and walked around the play yard and walked around by the lake, any place that would make me feel good. But I wouldn’t do what they wanted me to do.

Donc, en fait, ils voulaient juste se débarrasser de moi, alors ils l'ont fait. Ils m'ont laissé partir.

Q. Vous avez dit que vous avez vécu une période tumultueuse après avoir quitté le pensionnat. Comment était-ce pour vous, jusqu'à la mi-vingtaine?

A. I left school when I was in Grade 10. I couldn’t function in the public school, or what you would call a normal school. What was normal? I went to school with my cousins and they were okay. The bell would ring for this and that and they would go on their own. I couldn’t do that because it was like nobody was telling me what to do. Though I didn’t want anybody to tell me what to do, I couldn’t figure the system out and yet learn at the same time.

I was having to deal with some addiction problems with my parents at home and having a young brother to kind of maintain and look after who was going to day school, so I was having these problems at home, let alone not having enough food for lunch to go to school, but still trying to make it there and still trying to function in this new setting, I lost it. I just had to quit because I didn’t know how to be able to manage all of these things going around me.

And going from one classroom to the next at the beginning was horrible because I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t know what classroom. Nobody told me anything. After being told things for so long I was dependent on that. I had become dependent on it but I didn’t realize that.

Puis je suis retourné à la Réserve et j'ai suivi un cours de perfectionnement, le GED en 10e année, et j'avais dix-sept ans. J'avais dix-sept ans et j'ai fait ce truc. C'était comme, bien après ça, c'était une sorte de succès et j'étais heureux. Mais à l'époque, j'avais encore mes parents.

Ensuite, je me suis en quelque sorte impliqué dans l'alcool. Je suis devenu alcoolique, enfin pas tout à fait alcoolique à l'époque. Je buvais juste pour être avec des gens et des amis et des trucs comme ça.

When I was nineteen my mom got killed. This guy we knew shot her and my siblings were there and I wasn’t. Fortunately for me I wasn’t there. But the trauma of that stayed with me for a number of years. I became an alcoholic after my mother got killed. I didn’t have any children. It was just me to worry about.

But there were some things that kind of stayed in my head about my mother, about a year before she got killed, I was eighteen. She told me, “Leave this Reserve. There’s nothing here for you. There’s nothing to offer you here. You can go and find a job outside of here. Find work. Do something, but don’t stay here”, she said.

How can I stay on the Reserve? I was there for a few years but I was raised in a Residential School. Because I couldn’t remember much of my younger years, very limited recall I have of that, because I believe I lost a lot of what I could remember or did remember was because I was in the Residential School for so many years. When you’re in there and feel like you’re nothing, when you’re older as an adult of eighteen, you’re supposed to be an adult and have all your faculties about you and have your goals ahead of you, I had no idea what I wanted to be, let alone go out there and work. My mom said, “Go and work.” What do I do? What am I good at?

After she gets killed, shortly after she sends me off now I have no reason to want to work. My mom is gone, a major person in my life was gone. Sure, I had my dad, but my dad was kind of distant so it wasn’t like he was there emotionally. Physically he was there but emotionally he wasn’t. I had all these younger siblings. Throughout my life at different times I had to look after them the majority of the time, so now I’m eighteen, nineteen, do I want to continue to look after them? No. Even though I loved them I couldn’t even look after myself let alone look after them now.

So I forgot I had a life. Because I missed my mother so much I went into being an alcoholic for 6 years. During those 6 years it wasn’t a journey that people make alcoholism out to be. There’s a lot of emotional stuff going on, a lot of mental stuff going on. Because during that time I had no self-esteem. I didn’t know where I was going. I had no goals, let alone an identity. Who was I? I lost me somewhere along the way.

I didn’t even know myself as a First Nations person. It was difficult because I always wanted to be a success in something. At that time I only could dream. And one of my dreams was to go to university. But I thought that was impossible because I was an Indian. How do I function as an Indian in a White society? I only knew how through alcohol and to numb the pain.

When I seen a White person all I wanted to do was “What are you going to tell me to do now?” Because I couldn’t think for myself. I was always thinking they had to think for me.

Il y a des jours même maintenant où j'arrive en quelque sorte à cet endroit. Mais parce que j'ai la conscience de moi maintenant et que je reconnais ces moments, je peux me ramener immédiatement d'un épisode si j'y vais.

Residential School issues don’t really leave you. You work through them. You cry through them. You forgive and you let go. But sometimes automatically situations will come up.

I have 2 little girls now. When they were small I had it in my head that these kids knew. I just caught myself one day saying, “I told you once and once is good enough. I don’t need to tell you any more.” Then I looked at my girls. They were like little babies. One is 2 and the other one is 6. They are just kids learning. I had to remind myself. I told myself I can’t go there any more. I told my girls and I grabbed them and I cried because I remember being in Residential School.

We were always told once and we were never to be told again because there were repercussions and we didn’t want those repercussions. They would discipline us through straps, through hitting us with rulers, leather straps, put us in the corner, isolate us from the rest of the kids and make us sit there and watch them play —

It’s hard on a kid when you want to play. It’s torture.

— Speaker overcome with emotion

I couldn’t bring my kids up like that.

Q. Comment avez-vous trouvé en vous-même que vous avez pu élever vos enfants comme vous vouliez les élever?

A. I’m an older lady who had her children later in life. I had my first daughter when I was thirty-seven. My daughter is thirteen now. I had my baby when I was forty-one. But in between twenty-five and thirty-seven I was able to work through a lot of issues in regard to Residential School, my life and my self-esteem. I wanted children and I didn’t have any until later in life.

Being able to look back on my raising and how other people raised their children outside of a First Nations community, I was able to realize that the way we were raised was not normal. You see my first husband —

I was married twice. That’s another issue. I find that a lot of Residential School survivors and children have multiple relationships because we don’t know how to function as a normal individual. What is normal?

My first husband was a White man. I met him here and we moved to BC. I loved him greatly, but I didn’t know how to love him. He loved me. The way he loved me was different than I had ever seen in my whole life. He cared for me. He brought me flowers. He had gifts for me. When I would get home from work he would have a card and flowers on the table, or a little gift. Sometimes he would have dinner for me. Sometimes he would take me out to dinner.

I thought there was absolutely something wrong with this man. He’s not normal. I was always trying to make him fit into my normal. And my normal was more abusive.

Unfortunately that relationship came to an end because I was so confused. I didn’t know who I was, and I guess his patience ran out. He became my friend after, but he still is kind of like a milestone in my life because that’s where I had a lot of encouragement. Finally after the relationship ended I had to figure out who I was and where I was going.

We didn’t have any children and then I met my second husband and I have 2 children from him. That relationship was what I was looking for in my first husband, and that was horrible! There’s no pleasing me in any relationship. Right?

Finally I took a program in Vancouver in regards to family community counseling. I wanted to be a family community counselor, so I took this program and the instructor had her Master’s in Social Work, and many other degrees. She was an older lady. She said, “some of you here are going to drop out, for some of you your relationships are going to end.” And I looked at her and I said, “What are you talking about?” I was determined to find out what that was. And I did.

My relationship ended with my second husband, because a lot of that was experiential training where I had to take a look at myself. That’s where I worked through a lot of Residential School abuse as well, especially with the Nun in the Play Room. I didn’t realize I held so much anger and bitterness toward her, and unforgiveness.

It just kind of evolved one day. There was an older lady in my classroom. She had this way about her, these mannerisms were so particular and so peculiar. I can remember. Why does she stick out to me? Why is it I don’t like her? This lady comes from the coast and I had no clue who she was and I didn’t like her. I had no reason not to like her. I just didn’t know who she was. But the way she was carrying herself and the way she would talk, it would be so curt and to the point and so directive, I guess. There was no emotion behind it. And her facial expressions kind of matched her attitude and the way she was.

I kept questioning myself. Why don’t I like her? What’s going on here? Finally one day it just dawned on me. She reminded me of a Nun. Later on the program I found out she was raised in a Residential School for a number of years.

Q. Wow.

A. But that day I sat down and the Instructor said, “Don’t go home, Lorna, stay here. I think it’s time you started dealing with some of this stuff. I’ll give you some art therapy right here in the classroom. While the rest of the students work you can sit along here and do your art therapy.”

So I did. I challenged myself to do it because I didn’t want to be the way I was and I wanted to figure out why I didn’t like this woman. You know, it was so strange because I started drawing and I drew a scene of Lebret, this big school, along with the way of the cross going up to this little church, you know, and different things.

Tout d'un coup, je suis retourné à l'époque où j'étais une petite fille là-bas et je me suis souvenu de cette religieuse. J'ai commencé à dessiner cette nonne et tout d'un coup, j'ai attrapé le crayon noir et j'ai commencé à griffonner partout sur elle. J'ai commencé à faire cela et en commençant à faire cela, je pouvais juste sentir la libération de la colère qui était refoulée en moi. Je l'ai un peu perdu. J'ai eu une panne de courant.

Quand je suis arrivé, j'allais juste comme ça (indiquant) vraiment dur sur le papier. Et puis je me suis assis là et j'ai pleuré. J'ai pu pardonner à cette nonne et la laisser partir. Puis la dame est devenue mon amie.

Q. Wow.

A. But those kinds of things that have happened in the school, different places will trigger different things. If I was willing to let go of them then I have to work through them right away. I can’t stuff it any more.

J'ai quitté ce programme avec une personne plus légère. Attention, ma relation a pris fin, mais c'était bon pour moi et mes enfants.

Et mon rêve est devenu réalité. Je suis dans mon dernier semestre de mon BSW à l'Université de R.

Q. Wow.

A. So with a lot of counseling for myself, but not only counseling but also for my beliefs, I’m not a traditional person, I’m a Christian believer, and personalizing that and having a relationship with the Lord, with Jesus, the way I see it —

— End of Part 1

…brought me back to the school. Because they always deemed me the leader, I was the one who got the most severe punishment.

I got ten straps on each hand until I cried. I mean, like I wouldn’t cry. For the life of me I didn’t want to cry. But because the priest wouldn’t let go, wouldn’t quit until I cried, I cried. And the strap was about that thick (indicating) and it was a huge long leather strap. I always kind of think of it as what they used to use on harnesses for horses, quite sturdy straps. Yeah, that’s what he used. Because he deemed me as the leader I got the worst punishment out of it all.

But I said, “One day I’ll get you!” (Laughter) And that one day came when I became rebellious and I wouldn’t listen.

Q. Do you ever think of that day today when you’re sitting here and you’re in your last semester of school and you are having your dreams come true and you’re really somebody and in your heart you know how great you are? I hope you do.

A. Well, it took me a while to get to feel —

Well, I don’t even know if I feel like a somebody. But I’m a person who had to deal with all of those issues. Because not having your identity for a number of years, I only found my identity about 5 or 6 years ago. And being able to function in a society where you don’t have an identity is horrible because you are always trying to fit in.

In Vancouver I could be riding around on the bus, I could be riding around anywhere and because some people think I look Asian, or Korean or Chinese, you know, go down to Chinatown and walk into a store and they start talking oriental to me, or Mandarin, whatever. I would just be smiling at them and I would say, “I don’t understand you, I’m not…”

But then if I’m in the Italian area, depending on how I was dressed, I would fit in. But I would never admit to be a First Nations person for a long time.

Q. Wow.

A. Even though I went to First Nation functions and schools and stuff to get my education, when I left there I just kind of became somebody else. After I have done all that, I am proud to be who I am. I’m proud to be a First Nations from Carry The Kettle. I did research. I did history on that to find out my roots. Yeah, it was really awesome. It’s been a journey.

Q. Merveilleux. Merci beaucoup d'avoir partagé votre histoire. Je me sens chanceux de vous rencontrer.

Un merci.

Q. Thank you. Okay, we’re done, unless you want to say anything else.

R. Non.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac