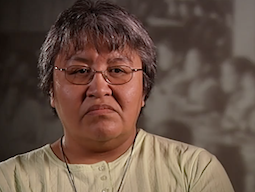

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

THE INTERVIEWER: Okay. I’ll get you to say and spell your first name and your last name so we can work on the audio level.

RICHARD KISTABISH: Richard Kistabish. Richard

Kistabish.

Puis-je d'abord dire la dernière partie de mon histoire?

Q. Oui.

A. I’m from Pikogan. I’m a member of the Abitibiwinni First Nation.

It’s funny that I do this in English.

Q. That’s okay.

A. It’s all right.

Q. Très bien, Richard.

R. Après avoir terminé mon école, je cherchais un emploi. Les Affaires indiennes m'ont offert ce poste appelé agent de liaison à l'éducation pour tous les Algonquins de la région de l'Abitibi. Une de mes tâches était de remplir ce formulaire appelé IA352. Ces formulaires sont les documents officiels que chaque parent doit signer pour que ses enfants aillent au pensionnat. Cela s'est produit en 1972 au printemps et en été.

During the summer months of that period I went to visit this community called Gitsikagik (ph.) Grand Lake Victoria. This community has no Reservation, no infrastructure, nothing. They don’t have land to have a Reserve for them. They are still nomads. They are still practicing the traditional way of life.

Un jour, il m'est arrivé de rencontrer le chef de cette communauté.

Dois-je dire son nom?

Q. Non.

R. Son nom, de toute façon, est Sam. C'était un vieil homme. J'imagine qu'il était un aîné de cette communauté en même temps. Quoi qu'il en soit, il était le chef, le chef. Il m'a vu quelques fois avant que j'aie cette conversation avec lui.

One day it was raining. It was really a bad weather day when I arrived at their camp, at their place. He asked me to get in his tent. I sat there on the floor with him and his wife was serving me the traditional tea. They had a big pot on the fire. He asked me some questions, but the lady there finds this man so offensive because we should make him eat first and then he’ll talk later. So that’s what happened. So I eat and after that I started to talk.

He asked me what I’m doing and all these questions. At the end I showed him the document; IA352. That was the most important document for me because from that document there was a statement made by the parents that they gave up all their responsibility. They gave this responsibility to the Queen, to anyone actually, where their kids would go.

He asked me to translate all the lines of that document. It’s 8 ½ by 14 on both sides. They have all those little characters that were in this formula. So I took the whole day just to translate every word in that document, both sides of the document. As I translated the wordings I realized at that time the wording that I use in my own language was so inappropriate or meaningless sometimes, or too powerful at the same time to be aware of what I was actually doing. I was taking away the kids by having those parents signing this document.

He made me realize that after questioning some of the wordings in there. He asked me why I was doing this. So I told him that it is part of my job. I’m being paid to do this job. That’s how I have my work. It’s that.

He asked me why. That was the first time that I tried to make sense of this word called “work”. I was not able to grab the meaning of that word in my own language. At the same time I realized that I’m going to be like the guys at the Residential School, the old thing, to take away their kids.

They took me when I was young, when I was 6 years old. It brought me back to that situation and I was starting to realize a little bit what I’m doing.

During that period of questioning and trying to answer the questions of this man I took some time off in order to think about it. We made some comments about my work there, but also about me being in school the first year. He asked me how was it and how I felt when I was in Residential School. So the whole thing, my whole day made me realize, I started to get conscious about the way I am, the way I feel or the way I’m supposed to be, I guess.

It was a big moment for me to be, I guess, starting to be aware of what I was doing. So at the end of the day —

When I arrived there it was about 9 o’clock in the morning. When I left it was ten at night. I didn’t realize the time during that period. I know at the end of the day when I left I told the chief that I was not doing this thing any more and I’m going to bring back all those forms to the office.

Je suis allé au bureau le lendemain matin et j'ai remis tous les formulaires aux Affaires indiennes et je suis parti.

So that’s the starting point of my healing journey. I guess I could say that, yeah, because that day was the day of —

I didn’t have any awareness, I didn’t have any soul maybe as a Native person. I turned back and I started trying to understand what it was I was doing there.

Then I was starting to be interested in what was going on, what happened, in that Residential School. So that’s the day I always remember because it was the time for me that I turned around and I started not a new life but a new way of thinking, a new way of asking myself questions before doing things.

Q. Alors, comment était-ce lorsque vous avez commencé à vous souvenir de votre voyage? Quelle est la première chose dont vous vous souvenez?

A. Lost. I was lost. Losing things. Losing stuff that I was not able at that time to point out exactly what I’m losing.

There was one thing I always remembered and it was that when we arrived on the first day at this Residential School, I was telling to myself there was a mistake somewhere that happened. Mom and dad couldn’t make that kind of mistake, they can’t make that mistake. They must be fooling around or they must have been cheated, or something. So I was expecting them to get me one of these days, like tomorrow or the day after. But they never showed up.

Until on my birthday, October 19th, I was lucky at that time because it was on Sunday. My parents were allowed to come and to visit me for a short period. It was really short. It looks like it was 5 minutes maybe. But the whole family came down with a taxi. As soon as I saw them I told them, “Just give me 2 minutes, I’m going to go get my stuff and I’m going with you, going back with you.”

That’s the most painful experience of my life on that day, on my birthday. Wow. I was stopped by the Priest not to go beyond the door to get where my stuff was. I turned around and I said, “That’s okay, I’ll leave all my things here and I’ll go back with my parents and my brothers and sisters.”

It didn’t happen like that at all. It was iee, iee —

It was very bad for me because when it was time for them to leave, when I turned around, I decided to go with them. I walked with them and I was holding my mom’s hand and my father was walking in front of us. I guess they knew at that time it was impossible. There was something that was going to happen there.

J'ai répété cette histoire à plusieurs reprises lorsque j'étais en counseling.

My mom went in the taxi and all my sisters and brothers were in that car. My dad was sitting in front. My mom was behind. I tried to get in between my mom and my sisters but I just can’t so I was trying to push my mom to move and to give me a small space for me. But it didn’t happen. So they just closed the door. Then I realized that there’s another mistake that happened. Why are they doing this?

I noticed that around the car the Priests, the Oblates, they call them le frere, they were around the taxi. The more I talk about this, the more I see clearly the picture of what was prepared for me. I guess they knew at that time I was going to try to leave with the family. So they closed the door and the window was open because my mom was starting to cry at the same time and she wanted to kiss me goodbye. I grabbed —

Vous savez quand la porte est comme ça (indiquant), un espace là-bas. Alors je l'ai attrapé avec ma main comme ceci (indiquant) et je le tiens. Le taxi commence à rouler. Je courais au début mais à la fin j'étais traîné dans la poussière. Je l'ai fait jusqu'à la porte comme ça. Finalement tout le monde arrivait, tous les prêtres et les religieuses arrivaient et ils ont essayé de me séparer le bras pour que je lâche le taxi et j'étais épuisé après quelques minutes de combats là-bas. Alors ils sont partis. C'était la séparation, je suppose, perdue.

Q. Que faisait votre mère pendant cette période?

A. I didn’t see her. To make things worse, the taxi was black. Wow. I never saw her after for a long period of time.

J'étais classé à l'époque comme le grand bébé. J'ai fait une scène. Je me battais. Je criais, pleurais, me battais et donnais des coups de pied, donnais des coups de pied aux pneus du taxi. C'était un gros combat. Je me suis battu très fort pour ne pas rester là. Ce sentiment était horrible à ce moment-là parce que je pensais que j'étais la chanceuse qui rentrerait bientôt à la maison, parmi les 200 enfants qui me regardaient ce jour-là faire cette grande scène, ce grand combat. C'était si dur et si douloureux à la fois.

It was a big loss. I don’t remember the days after this in my mind. I’m trying to figure out what happened because —

— A short pause

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous êtes entré pour la première fois? Te souviens tu?

A. Six.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous êtes parti?

A. Seize ans.

Q. Seize ans. Quand tu étais à l'école, t'es-tu souvenu de quelqu'un d'autorité qui aurait pu être gentil avec toi, comme t'a fait un câlin et t'a dit que tout irait bien?

R. Non.

Q. Jamais?

Un jamais.

Q. Et les autres enfants? Avez-vous un ami dont vous vous souvenez?

A. It seemed that we were kind of scared or afraid. I don’t know exactly what that was about, about friendship. We knew each other, most of us, but we never had a chance to do things together before going in that school. Between the ages of 1 to 6 there’s not much of a relationship that was being developed between us because of the way we were living. We were nomads. We were traveling by canoe so we were on the trap line most of the time. During the summer months we were camped beside the church.

Q. Avez-vous eu l'occasion de rentrer chez vous pendant l'été?

A. Ouais.

Q. Alors, lorsque vous êtes rentré chez vous, avez-vous développé une résistance, une résilience presque pour devenir plus forte pour quitter à nouveau votre mère et votre père? Cela vous a-t-il rendu plus fort?

A. When I had a chance to go home after this trauma that I had with my mom and dad and my sisters and brothers saw me, they were witnesses of the thing that happened, when I go home I didn’t feel the home. I didn’t. I went there because it was the only place that I could go, I guess. The sense of the joy of returning home was great when I was in that school. But when I arrived all this joy and dreams that I had to be home again was not there. It was gone. It was as if I just had time off at Residential School, just as if I had another space to be around for awhile until I get back to school.

I had a really hard time to say that I’m going to be here for the rest of my life, to stay in the family. I knew it was over at that time. It was no use for me to have some dream of being family again and being with my brothers and sisters again for a long time because I’m going to be away again. So I didn’t have that feeling to be connected again with my family. It was a strange sense of life to be like that. You are in your family and you don’t feel the family side, the family sense. I had a really hard time to cope with the situation. I knew at that time it was going to be like that for a long time.

Q. Et vos frères et sœurs? Étaient-ils aussi à l'école?

A. They went. They went to school. Two years after me my younger sister came with me. But I didn’t see her the whole year.

Q. Pourquoi cela?

R. Nous étions séparés; les filles d'un côté et les garçons de l'autre.

Q. L'avez-vous recherchée?

A. Of course I looked for her. But we were not allowed to communicate. I remember one time —

I don’t know why they did this but there were lots of people that had sisters in that Residential School. One time only, I remember this, we were allowed to speak to our sisters in that school. It was done in the corridor, in the hall. One side is the boys and the other side would be the girls and we were trying to find a spot to be able to communicate but with a person walking right in the middle of the alley. That’s the only time I met my sister and I was not even able to talk to her, just to look at her. And she doesn’t want to look at me.

— End of Part 1

Q. Donc, avant d'aller à l'école, votre sœur que vous avez pu voir dans le couloir, avant d'aller à l'école, vous et elle étiez-vous assez proches?

R. Avant d'aller à l'école, oui.

Q. C'était votre petite sœur?

R. C'était ma sœur cadette, oui.

Q. Vous devez donc l'avoir complètement adorée?

R. À ce moment-là, oui. Et mes frères aussi, Monnnie (ph.) Et Jojo (ph.). Nous sommes dix dans la famille.

Q. Wow. Alors quand tu es sorti de l'école et quand elle est sortie, est-ce que ce même sentiment était toujours là?

R. Non.

Q. Où est-il allé?

R. Je pense que la séparation, être séparés comme ça, était un fait que nous supposions qu'il serait là pour le reste de nos vies, je suppose.

We are just starting to try to connect over the past few years now, but it’s so difficult. It’s not hard but it’s so unnatural, I could say. It’s not part of us any more. It’s not there. We know we are brothers and sisters but that’s about it. We don’t communicate with each other. We don’t know what is going on in the life of the other ones. We know we have kids, but that’s about it. We don’t have that kind of warm relationship.

J'ai perdu 2 de mes sœurs il n'y a pas longtemps, il y a une dizaine d'années. Deux d'entre eux sont décédés à cause de l'abus d'alcool.

Q. Avez-vous déjà eu l'occasion de ressouder cette relation avant leur départ?

A. Yeah, we had an opportunity to develop that. But every time that we tried to organize something to reconnect again as brothers and sisters, we always had the booze and the dope that gets involved in those things. It kind of freezes our feelings, I guess, about the relationship that we’re supposed to have. Even after some of us went for treatment and healing journey stuff, it is not there. It’s not there. The relationship that we’re supposed to have as brothers and sisters is not there. It’s as if this thing is not reachable again.

There was so much destruction that happened. I guess it’s too much bad things that happened to each one of us that we cannot express our feelings towards each other.

Q. Est-ce que cela vous a affecté en tant que père avec vos propres enfants?

A. Yeah, I think so. I’ve got 2 bunch. One with my first was my older kid, she’s thirty. I just found out yesterday that she was thirty! And my boy is twenty-five. My family relationships with my wife was not good at all. After 3 kids I decided to leave. And then I was not able to have a family, the normal family. So that was really bad for them, for my kids, for me to be like that, for me to leave them just like that.

I’m trying to reconnect now and we have much more of a good relationship now because of the healing process that I went through. I’m trying to recuperate the years that have been missing with them, and also trying to build some kind of relationship with my kids, trying to be a father again, trying to be a good father again. It’s really hard. Sometimes they blame me for the things I have done and they are right to blame me. I guess I have started to accept the consequences of this thing that happened to me and to them also.

C'est difficile.

Q. Is there another memory you would like to share with us, something that might have happened at school? Is there anything else, whether it’s good or bad that kind of stands out?

A. Poison. Medication or drugs, whatever. One time 3 or 4 years after the opening of this Residential School, everybody, all the kids in that Residential School were sick; 200 people sick in bed. One of the things that heals us from that sickness is the one that spoke French words will heal first, or will heal faster. It happens like that. Then when the people heard about this new medication, when you speak French you’re going to heal, you will be no more sick. Then you can go out there again. We were lying in our beds for days, weeks. And then we started to speak French and a miracle happened. We were alive again. That’s why I always have that impression that we have been drugged. We’ve been experimenting with some stuff for those.

For myself I lost 3 days of my life at that particular period. I went to the Infirmary, the nursing place. It’s not the same spot as where we sleep. It’s another place. I know I went there for 3 days and I don’t remember anything about the 3 days. It’s a black thing. I know this because some of my friends told me that I was away for 3 days and they asked me if I was sent away, if I went away to another place.

But I don’t know if I went to another place, but I know when I lost consciousness I was in that room, and when I wake up I was in that room, but it was 3 days later that I wake up. So I don’t know what happened during that period of time. But there was nobody who was sick any more when I came down after I woke up.

Q. Mais tout le monde parlait français?

R. Tout le monde parlait français. La plupart d'entre eux parlaient au moins une phrase de français après cela.

Q. Wow.

R. C'était incroyable. Nous commençons à être des étudiants modèles.

J'étais bon. J'étais vraiment bon à ce moment-là parce que j'ai terminé premier. J'étais le premier de la classe et j'étais mannequin à l'époque. Je savais parler français.

C'était jusqu'à la 7e année à ce moment-là, on pouvait aller, mais après cela, quand on voulait aller en 8e, il fallait aller au centre-ville, à Amos. Mais vous devez quand même vivre au pensionnat. Nous avons donc parcouru ces quinze kilomètres par jour.

And we finished first, always first class in that school. When I came out of Residential School after ten years I was allowed to live with my parents and continue to go to school. Still then I didn’t have to work hard to get those notes to be first in class. This thing to be first in class made the White students really mad at me. I’m better than them, an Indian guy. It was good. That was the good thing that I had from Residential School, the only good thing I guess.

But I think it was a matter of survival also to have good grades and not to be bothered by those people. Just do your thing. If you get first you’re not going to be punished. I was trying to survive.

Q. Nous entendons des histoires de différents types d'abus. Vous avez parlé de la violence psychologique et de la violence mentale en dehors de votre famille. Et les autres abus? Avez-vous vu quelque chose?

A. Yeah. The beatings. Sexual abuse, too. Oh yeah. I was a witness of those abuses, especially the beating and the humiliation. Some of my friends pee’d their bed during the night. So they have to walk around all day with their blankets on them, the whole day. Beatings happened really often, daily. Some of them are always the same ones who got beat up.

I know that most of the people that I know and I saw them get beat by the Priests, all those people are dead today. They are not alive, and they were the same age as me and younger. They didn’t make it.

Les abus sexuels étaient également quotidiens. Tous les soirs, devrais-je dire. C'était terrible de voir ces jeunes garçons entrer dans cette pièce. Nous nous demandions toujours: que font-ils dans cette pièce?

Q. Quelqu'un en a-t-il déjà parlé?

R. À moi; non. Non.

Q. Mais quand les garçons sont sortis, ils étaient tristes?

R. Ils pleuraient. Ils pleuraient. Nous ne pouvions rien faire pour les aider, je suppose.

There was also this guy —

His skin was so dark. He was a good hockey player, not better than me, but he was a good hockey player. We were chosen to go to the first Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament in Quebec City. You know that big thing in 1959. I was ten or eleven at that time. There was a team from —

C'est une bonne histoire.

There was a team from Amos. That’s a city about fifteen miles from that place that was looking for another 3 Indians to play together and to be part of that team in that city, Amos. So I was one of them, and Marcel and Matthieu. Marcel was the one who had really dark skin, really dark. He looks like a Black guy. After being officially chosen and officially that we were going to Quebec City during that period of time, the Priest decided they had to change the skin colour of Marcel because he was too dark.

So what they did, he plants the guy once a week in water with Javex. Every time that we take our shower this guy was always missing. We didn’t know why he was missing and suddenly we find out that he was up to his neck in the water with Javex, trying to turning him white. That was terrible. This guy got crazy after a while.

Q. Marcel l'a fait?

A. Marcel was his name. He believed that he was a White man when he left. He said the colour of my skin is no more a problem because I’m White now. He believed that for a long period of time that he was a White guy. He was a good hockey player but he didn’t make it.

Je suppose que le gars est mort aujourd'hui. Je n'ai jamais entendu parler de lui après ça.

Q. Wow. That’s crazy.

A. They made him believe that he’s White.

Q. But you don’t know if he is alive today?

A. No, I don’t know that.

Q. Pauvre Marcel. Ils l'ont juste fait se tenir debout dans Javex?

R. Ils l'ont mis dans l'eau de la baignoire. Des nuits comme ça dans cette baignoire.

Q. Juste pour jouer au hockey?

R. Juste pour jouer au hockey avec nous, avec les Blancs. (Rire)

On jouait contre Guy Lafleur à ce moment-là. Guy Lafleur avait 9 ans.

Q. Okay. So we’ll wrap this up. Just one more quick question.

Si vous pouviez résumer votre expérience de ce que les pensionnats indiens représentaient pour vous en une phrase, quelle serait-elle?

R. Perdu, je suppose. Perdant.

Q. D'accord. Merci.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac