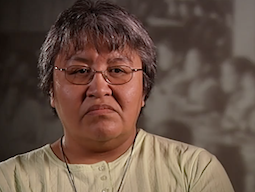

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

L'INTERVIEWEUR: Pourriez-vous s'il vous plaît dire et épeler votre nom pour nous?

WILLIAM GEORGE LATHLIN: Je m'appelle William George Lathlin;

William George Lathlin.

Q. Dans quelle école êtes-vous allé?

A. Tous les Saints. Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert.

Q. C'était le prince Albert?

R. Ouais, Saskatchewan.

Q. Était-ce une école catholique?

A. Anglicane.

Q. Quelles années y êtes-vous?

A. 1950 à 1954.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous avez commencé?

A. I was actually nine but my parents lied so they wouldn’t put me in with the smaller kids so they said that I was ten.

Q. Vous aviez neuf ans, mais vos parents ont dit que vous en aviez dix?

A. Ouais. Mon certificat de naissance dit que j'avais neuf ans à l'époque.

Q. D'accord. Vous rappelez-vous comment était la vie avant d'aller à l'école?

R. J'ai vécu avec mes grands-parents, mon grand-père d'abord et ensuite ma grand-mère, pour m'apprendre la langue, je suppose. Vivant avec ma grand-mère, nous avons mangé de la viande séchée, du pemmican, beaucoup de viande et de poisson d'orignal et tout ça. Elle m'a montré les médicaments et tout ça.

Q. Vous avez eu une éducation traditionnelle?

A. Ouais. Elle m'a montré les médicaments et je devais aller déterrer des racines, des herbes et des trucs comme ça pour elle à un jeune âge avant d'aller au pensionnat. Pour moi, c'était une vie bien remplie à apprendre.

My dad used to show me how to make fish nets. I didn’t know what I was doing. He gave me some tools to measure and I didn’t know I was making fish nets.

And my grandmother, when we finished smoking the meat and all that, the fish, she would put it in a bag and she gave me something to eat it with. I didn’t know I was working and preparing my food and making pemmican and all that. We would gather up —

Nothing was wasted when my grandmother was handling fish. Nothing smelled bad, even all that meat. When I was in the house we lived in you wouldn’t find no food on the table. You would think we had no food but it was hidden underneath the building where it’s nice and cold. But there was nothing to spoil. That’s what I remember.

À l'époque, avant d'aller au pensionnat, j'allais dans une école de jour ici. Je marchais environ un mile d'ici à l'école, que ce soit en hiver ou en été.

Q. I think we’re just going to stop for a second because of the background noise.

Ah oui.

— A Short Pause

Q. Alors pouvons-nous parler un peu plus de votre enfance avant le pensionnat, peut-être parler un peu de la chasse que vous avez faite.

R. Quand je vivais avec mon grand-père, je regardais passer les bateaux à vapeur, avant de vivre avec ma grand-mère. C'étaient les moments tranquilles et paisibles dont je me souviens, à regarder depuis le pont. Les gens se sont précipités vers le pont et le bateau à vapeur est arrivé et ils ont ouvert la travée centrale du pont pour que le bateau à vapeur puisse passer. J'aimais regarder ça.

La plupart de ce dont je me souviens, ce sont des activités de piégeage pendant la saison de piégeage. À différents moments de l'année, nous sommes allés à différents endroits pour chasser et pêcher et tout ça. Alors, quand j'avais sept ou huit ans, je suis allé chasser et piéger.

— A Short Pause

We were out west here. My dad had a trap line. When we went out of course we had to haul everything out by horses. Horses took us out there and the whole family went. The first winter there I got my first mink. I don’t know how old I was, seven or eight years old. My dad gave me a .22 and I shot my first deer, a great big buck. It had horns and all that. And the next one I got my first —

Alors je suppose que j'ai appris à être chasseur et trappeur à l'époque parce que mon père m'enseignait.

In the spring time he said you have to go and learn another language and learn how to read and write and do arithmetic. I didn’t understand what he was saying. So he said you may have to go away for a while. So I didn’t know where I was going. I knew that my cousins, Walter and Albert Lathlin were away in school at Elkhorn at that time.

But then they came back and said we’re now going to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. So they were telling him I guess —

Like I said, I was nine at the time and they told him no, that’s too young. They’ll put him in a place where they lock them up. Say he’s ten. So I guess that’s what my parents did. They said I was ten. So they put me in another category when we got to Prince Albert. Around August they put me on the train with the kids. My sister and I were eager and they sent us.

We travelled all night by train and we were met by some people and put in a truck and when you got to the place where we were going, they unloaded us. The little ones went somewhere else and the medium-sized people and the older people. I went with the medium-sized people. I guess you called them Intermediate boys, or something like that. The little ones, I found that they were locked up after their schooling, whatever. They weren’t allowed to go anywhere. But at the Intermediate level we were allowed to go.

This is where I didn’t understand what was expected of me because I didn’t speak the language. It was very difficult for me to comprehend what people were asking of me. But anyway, I watched the kids and that’s how I followed what they did.

So they took us there and assigned us beds and numbers. I think my number was “214”. They assigned us beds. The clothes were on there. I don’t remember if they gave us a haircut first or later, but they made us take a bath. I think there was a haircut first. I don’t remember.

But then they put this white stuff on my head I had to kind of wash that off. It was my first time being in a shower room with a bunch of kids naked and all that. To me that was the first shock that I had. People say it’s culture shock and I guess from there —

But I wanted to learn. I wanted to find out more about what my dad had said about school. “Try and learn as much as you can.” So I tried.

La prochaine chose que je sais quand je suis revenu, mes vêtements étaient tous partis et j'ai dû mettre d'autres vêtements et tout le monde était pareil. Bien sûr, au début, j'ai raté mes vêtements et tout ça.

They stripped the bed and said, “Here, you’ve gotta learn how to make your bed.” So I tried to make it. I was watching the kids and I didn’t know what they wanted of me. But I was watching them and they were making their beds so I did the same thing. The ones that did it right they were let go and me I get caught I don’t know how many times. I guess finally I got it right but there were a lot of times before I got it the way the other people make their beds.

Quoi qu'il en soit, c'était ma première leçon, ma première leçon.

Of course I didn’t speak English. I spoke only Cree. When I was washing up I would talk in my language and the supervisor would find me talking and give me soap, Lifebuoy soap. He said, “you —

So I ate it. I ate this Lifebuoy soap, you know, you wash your —

I didn’t know why. Why was I eating it? But I guess it was because I was speaking Cree. But it’s the only language I knew.

In the classroom the same thing happened. I learned. I tried to learn what they were trying to teach me but at times I couldn’t understand what they were saying and they would come back and hit me on the side of the head. They kept hitting me until I did what they —

I guessed what they wanted from me. That’s what I tried to do. I just guessed because I didn’t understand what they wanted of me. That went on and on. Somewhere in the winter time of that year my ears started to —

There was this yellow stuff coming out of my ear and covered my pillow. I guess I smelled awful. The kids started calling me stinky. That’s my nickname today because of that. I guess something happened to my ear.

Q. Est-ce que l'une des personnes qui y travaillaient l'a regardée ou avez-vous reçu des soins médicaux?

A. No. I didn’t get nothing. Again, I didn’t know what to do because I had never been away from home. I didn’t know the language. I didn’t know. I just suffered through it because I didn’t know the system or nothing, being away from home for the first time.

Anyway, that went on through the year. As it went on I became deaf. I couldn’t hear no more from this ear. So it made my learning the academic stuff that much harder, again because I couldn’t hear. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t understand. And then I couldn’t hear with my left ear so it made things worse for me. People would think I was not paying attention or not trying to do what they were telling me but it was because I couldn’t hear or understand. They were trying to make me do what I didn’t understand. It was awful.

I get mad when I think about that because people shouldn’t be treated like that. If I had known what they wanted I would have done it. If I had heard and understood I would have done it.

Quoi qu'il en soit, cela a continué. C'était la première année, 1950.

The kids picked on me. They kicked me. They beat me up. I would just whimper. I couldn’t cry no more. That went on throughout the year, and that was the first year, again.

Q. Les enseignants ont-ils déjà vu les autres enfants vous battre?

A. No. This was when we were outside the school. There was no supervision to tell you the truth. All I seen the supervisor was in the morning and time to go to bed at night. That was it. I didn’t see no one. There was no supervision.

I found something. I found a hole in the building, a crawl space, so I went in there and that’s where I hid. That was my home. On the weekends I went there and hid. I didn’t want the kids beating me up. Again, that was the first year.

But the second year, later on in the summer time I got tired of that and I said, “that’s it, you guys beat me up and made me cry but you’re not going to make me cry no more.” So they beat me and I didn’t cry. But I said, “I’m going to hit you as much as you hit me. I don’t care how big you are.” And that’s what I did. Every last one of those guys I went and hit. They were bigger than me but I hit them as much as they hit me. Pretty soon nobody bothered me. That’s how I defended myself.

I got a bad reputation later on. You don’t bother that guy. I didn’t feel the pain after. When I said, “You’re not going to make me cry no more”, the pain, the physical pain I didn’t feel it. It didn’t matter if you were hitting me. Sure, I got a licking, but I didn’t feel the pain.

That affected me through my adult life because I couldn’t cry. I had a hard time crying because I made that statement that nobody would make me cry, in public. But I cried when I was alone. So that was the first year.

Again, in the first year, some time in the winter time I found myself tied up. They had double-decker beds. My legs were tied up and my arms were tied up like this (indicating). There was two people standing on each side of me and played with my penis and it hurt. I didn’t know what to do.

Q. Cela s'est produit également la première année?

A. So I pretended it didn’t happen and I guess I fell asleep. But in the morning when I woke up and went to the washroom it hurt because I was bleeding. I don’t know who those people were but I knew I was tied up. It never happened again. But I didn’t know how much damage was done to me until later on in my adult life.

This one here, my ear, again I couldn’t hear. I could just smell myself.

La nourriture, comme je l'ai dit, quand nous préparions notre nourriture, rien ne sentait.

On Fridays we had fish and that fish smelled. I didn’t eat it because to me when something smells bad you don’t touch it. As I said, from my grandparents, you know, I didn’t touch it even though I was hungry.

Un petit-déjeuner typique consistait en une tranche et demie de pain coupé en triangles, trois petites demi-tranches, puis une bouillie diluée et du lait en poudre.

Q. Avez-vous toujours eu faim?

A. I was never full. Never full. Again, later on —

This was the first year again. I was hungry. But I didn’t know —

People ask me, “Do you know these people?” I didn’t know anybody. I was totally in shock for the first year of all the things. I had never experienced anything like that.

Q. Comment était-ce de rentrer à la maison après cette première année? Avez-vous dit à vos parents quelque chose de ce qui s'était passé?

A. No. I couldn’t fit in. I couldn’t fit into the community. I felt alone. I felt that they had abandoned me. I felt the trust that I had was not there so I couldn’t tell nobody. Everything went inside.

Q. So it wasn’t the same at all when you went back?

A. No, it wasn’t the same.

Q. Étiez-vous en colère contre vos parents de vous avoir envoyé?

A. Yeah. I didn’t understand that they had to send me, not until later, when I was older. They were forced to send me and then I understood.

Q. Et votre deuxième année à l'école?

A. My second year I learnt to speak a little English but then I kept getting hit on the side of the head for not hearing and not really understanding what was expected of me, by the teachers. I would get a strap because I didn’t know what they wanted.

Q. Votre première année a-t-elle été la plus difficile?

A. That was the hardest because I was not able to speak for myself or know how to protect myself. I just learned as I went along with the other kids. It prepared me, I guess, for the second year and third year. I knew if I was to survive I had to do things, take control of things myself, in terms of —

I had to survive: number one. The best way —

If I didn’t have enough food then it was up to me to find food for myself.

And cold. I was cold all the time because I didn’t have enough blankets to cover me. I was cold and hungry and lonely, no one to talk to, no one to communicate with because I didn’t know anybody the first year.

Q. Avez-vous déjà vu votre sœur?

A. Once in a while I would get to see her. My dad would send us some stuff and she would come and give it to me. I think in the first year I saw her twice. That’s it.

Q. C'était agréable de la voir?

R. Oui.

Q. Qu'est-ce que votre père a apporté?

A. He would send a package, like bannock —

Disons, par exemple, des chaussures. Il m'envoyait des chaussures et des trucs comme ça et un peu d'argent.

Q. Aviez-vous hâte de voir ces cadeaux de votre père?

A. Ouais.

Q. We’re just going to change the tape. I want to talk to you about life after Residential School.

— Transcriber’s Note: Tape was not changed.

Q. J'aimerais donc parler de la vie après les pensionnats indiens, mais si vous pouviez simplement raconter cette histoire sur votre main, ce que vous avez fait la deuxième année et ce que vous avez ressenti.

A. Okay. In the second year after all this negative talk about Indians being no good and the only good Indian was a dead Indian and all that and everything that the Indians did was evil and all that, the way they prayed and so on, it affected me. My skin was kind of brown and I tried to wipe the skin off my left hand. You can see the scar today. It’s still there. It was all red. It really messed me up because I didn’t —

I couldn’t figure out why my family, my grandparents and my mother and father were called evil and what they did was evil and all that. I couldn’t. It messed me up in my thinking. It messed up my thinking. I didn’t know it affected me that way at that time because I was just a young fellow and all that. I was not even an adult yet. It bothered me I guess in a way that I despaired in my mind and the way I was brought up, there was a clash there of cultures, I guess.

I was lucky that I was able to maintain my language, to know and understand that we are different from other people and we have our ways and we are closer to the Creator than any other race of people that I know because I’ve come back to my roots. That’s what probably saved me from really destroying myself.

I thought about committing suicide. I tried it. I turned to alcohol. After I got married —

I figured by getting married I would settle down so I started having children and all that. But things got worse. I was running away from something and I didn’t know what it was. I went on a drinking spree for seventeen years. Finally I said “there’s something wrong with me”. I was seeing a psychiatrist and a doctor and he gave me pills. I was actually addicted to prescription drugs, too, because I was feeling all this pain in my body and my mind.

I was working at the mill. I had a job there, a steady job. I became apprenticed there. I became a millwright, a certified millwright. But my drinking kept on for seventeen years. In ’78 I decided to do something with it. I went down to see a doctor. He sent me to a Treatment Centre and that’s where my journey of healing I guess began. I didn’t know about the sobriety part, anyway.

Q. De retour à l'école pour une minute parce que vous avez pratiqué votre spiritualité traditionnelle à la maison, comment vous sentiez-vous d'avoir à aller à l'église tous les jours? Êtes-vous allé tous les jours à l'église?

A. No, just on Sundays, twice on Sundays. There was something different where all the people, the old people that were around at that time, the Elders and all that, a lot of them prayed. In the other place there was only one person in the front speaking. Once in a while we were allowed to sing or speak. That was the difference. And then they had this —

They were praying to a god I didn’t understand and it was the son they were praying to. I didn’t understand that. And then they had this book that they were reading from which I came to understand was the bible. The bible itself and the words that are in there are a lot different than what our teachings are. You know, I found that out. I came full circle. But the people I guess were trying to do the right thing. I didn’t know that either.

So I forgive those people. I forgave those people that harmed me in so many ways. But I can’t forget what happened.

Q. Alors, à quoi ressemblait la vie juste après le pensionnat lorsque vous êtes parti en 1954? Qu'as-tu fait juste après le pensionnat?

R. Je suis retourné à l'école ici à l'école de jour. J'ai été viré de là parce que mon père est tombé malade et que j'ai dû aider ma mère et élever les autres enfants. C'était dur. Il n'y avait pas de bien-être. Je suis devenu un père instantané, je suppose, aussi. J'avais quatorze ou quinze ans à l'époque. J'ai aidé ma mère à élever trois autres frères et sœurs. Il y avait quatre d'entre eux, deux sœurs et deux frères.

Nous avons fait de l'argent en tannant les peaux d'orignaux. J'ai fait la pêche et le transport de l'eau et la pêche et tout ça. Nous avons donc survécu à cela.

Mon père est revenu à l'adolescence alors je suis allé travailler. En fait, je travaillais quand j'avais quatorze ans. Je gagnais 50 cents de l'heure, mais c'était suffisant pour acheter de la nourriture, des vêtements et tout ça.

By the time I was in my twenties, like I said, I found myself wandering around doing nothing. I had all these women around me, chasing me and all that so I finally decided to pick one and get married. I asked her if she would marry me and she said, “Okay.” Well, let’s get married. So we got married and we’ve been married since ’61, and we had five kids.

I provided everything for those kids except love and nurturing because I didn’t know what that was. It was buried inside me. I couldn’t teach them that. So they are suffering with their children.

Q. Avez-vous déjà pu leur parler de votre pensionnat?

R. J'ai écrit ce qui m'est arrivé, mais j'espère que cette bande aura une signification plus profonde parce qu'ils le verront personnellement en en parlant. Mais je leur ai montré. Je les ai vus. J'ai écrit ce truc et ils l'ont vu par écrit. Ils savent.

Bref, où étais-je?

Q. Vous alliez parler de votre parcours de guérison. Quand cela a-t-il commencé?

A. My healing journey started in 1978. Like I say, I was onto prescription drugs and alcohol and all that. I didn’t know what was happening to me. There was something wrong with my life. I got to the point where what I was taking had no effect on me. The more I drank the sober I got.

So I went and seen a doctor. He says, “I can’t help you but maybe AA can.” So he sent me to (something) House and that’s where I learned about alcoholism. That’s where my healing journey began. I’ve been searching for me all through those years. They helped me quite a bit. In fact, a whole lot.

But in the meantime I had security. What I wanted was a meal ticket. It took me ten years. I became a tradesman, an industrial mechanic. I worked in the mill for eighteen years. But again there I faced something called racism because I was the only Native person there and all the other people were different nationalities, and White people and all that. They talked about me and I would be just shaking. I couldn’t understand why, why I was like that.

But the good part is I became the Shop Steward in the Union. I went as far as I could with my limited education. In Residential School I didn’t have time to learn academics because I was traumatized from Day One. I just lived in fear.

The fear. I didn’t talk about the fear. I didn’t know I carried that fear all those years. It came out one day when I was hunting with the van. I started shaking like this. My partner had gone out. He seen a moose run across and he’s chasing him. I’m sitting in the truck and I’m just going like this (indicating). I had my rifle here. What the heck is happening with me?

I’m thinking I’ve got to get control of my mind because if I don’t I’m going to do something awful. I might shoot myself. So I go around the vehicle and went and sat down there and I tried to relax. But from that day on the fear was in me. I started to sort out that fear. Why am I like that? I found out that when fear has control of you there is no love in you no more.

Q. Savez-vous pourquoi il est sorti à ce moment-là?

A. I could not understand why. But I guess all the love had drained out of me. I had given all I could to other people. In that sobriety thing I gave to people and got nothing in return. It drained all that out of me and the fear came in. That’s when I understood I was running away from something. I went and searched for that and I found it in the Residential School experience. That’s where I went, back to that.

But I did some good things. I was a counselor for the (something) Band for many years and I became Chief. I did a lot of good stuff for the community but I told the people I don’t want my name printed anywhere or people using my name. I did it because I felt it had to be done, not because of the glory or a name. You won’t see my name anywhere because I told the people not to put my name anywhere.

And then I tried to bring back healing in the community because of all the Workshops that we had done, that came to the Residential School experience, the second, third and fourth-generation people, they were stuck in that mode. They couldn’t go nowhere. I wanted to tell my story.

When I was invited to a Court Hearing to find out —

We were allowed to go to court and all that. That’s when I knew that I had these things buried in me and I had to get rid of them. When the lawyer said that these things never happened to these children, oh, I got mad because I knew it happened. It happened to me.

Q. The lawyer said it didn’t happen?

A. He said, “These things never happened to these children”, in front of the courtroom. I got really upset and mad over that because I knew they happened to me.

What I’m saying to you is what I experienced. It’s not something I picked out of a comic book. It’s my own experiences that I went through. But again it taught me to be resilient and to pursue I guess —

I wanted justice. That’s what I want. I want justice. And also to do what is right because I feel that our People out there are decent people. They are honest and they will do the right thing to remedy this because it should not have happened and it should not go on. It should be fixed, fixed by recognizing us as who we are. We are who we are. I cannot change who I am.

But I know that the Creator is with me and guiding me every day. And I want to pass that message on. To forgive is good but to forget I can’t forget it. It’s in me. You see this scar here (indicating). That’s the first year, too, a physical scar. I got hit with a stick on my eyebrow here. I forget now, but it’s there.

— End of Part 1

Q. Combien de temps avez-vous été chef?

A. Just two years. I wanted to get out of politics. But the people didn’t want me to leave so I was out in ’99.

Q. ’97 to ’99?

A. Um-hmm. Mais avant cela, j'ai été conseiller pendant vingt-quatre ans.

Q. Vraiment? As-tu aimé?

A. Ouais.

Q. Mon mari vient d'être élu conseiller.

A. Ouais.

Q. I’m a counselor’s wife.

Un bien.

Q. He’s busy.

A. Ouais. C'était dur. Les gens étaient toujours sur mon cas. J'ai été l'un des premiers gendarmes spéciaux du pays dans cette collectivité.

Q. Oh wow. Quelle année était-ce?

R. C'était quelque part dans les années 60. J'oublie. Ils avaient ce programme de gendarmes spéciaux et j'étais l'un des premiers. Pas de véhicule. Juste à pied. C'était une réserve sèche à l'époque. Mais c'était un bon salaire à l'époque; quatre-vingt dix dollars toutes les deux semaines.

Q. That’s not bad for the sixties.

A. Ouais. C'était bon.

Q. Okay, so maybe we can talk just a little more about just that turning point for you, when things turned around. You said you went to AA and maybe I think you had said before —

A. Yeah. As I said, I gave lots to people in their sobriety and all that. Finally I had nothing left in me and I became fearful and traumatized. Not knowing what to do, again I turned to my Creator and asked for help. But it didn’t happen overnight. It happened for quite a while. The fear sort of went away.

I couldn’t wander by myself I was so afraid. I was working at the mill, shift millwright, and I was working at nights. I would drive back from the mill about a mile to where I lived. It was frightening because I was alone.

That’s when I learned about love. Fear is the absence of love. So I had no love in me. That’s something that I didn’t know. I shut out everybody. I shut out everybody and everything was inside me and I had to bring that out. That’s what I tried to do. I tried to bring that out.

Where I found it was in my old traditional ways, peace and quiet and all that. Just before I became —

Well, I was Acting Chief. Before I became Chief something happened to me. I had to go to Vancouver. There was an election over there and I went there to Winnipeg for three or four days before the flight. I was in my room and I was walking around. I come back and I seen this thing on my bed. Of course, I’m fearful of things, eh. I opened it up and here’s all this medicinal stuff.

I don’t know what to do so I go see one of the traditional people and he says, “These are for you”. So I took them with me to Vancouver. But my dad had told me you don’t play with these things. They are sacred. So in practicing that there was a lot of stuff coming to me and my wife became afraid. So I didn’t know what to do. So again I asked one of the traditional people to help me and he said, “Put it away for a while.” So I gave it to him. That’s one mistake I regret. But he says, “That’s yours, you can get it back again.” But I don’t know how. I never had a pipe or nobody showed me what to do with it and all that.

But I have since learned that to know yourself you have to know seven things about you. You have to look up to the four directions, inside, and seven ways. That’s how you pray with the pipe. I didn’t know that then but now I know. So I missed that. That’s one thing I’m missing. I kind of feel alone because that pipe that I set aside was really mine but I didn’t know what to do with it when it came. Go and learn about my traditions and all that.

But I have since discovered that the greatest thing we have is in here. What we see is different than what is inside you. Our subconscious mind knows all and sees all. So when people say they lost everything, they haven’t lost nothing. It’s in here (indicating).

And it’s carrying on, too. When I go in the sweat lodge that stuff comes to me. It just comes. So people who say they have lost their traditional ways, they haven’t lost it. It’s in us. It’s in me. I know that. And the Creator, he’s in me. He is, because that subconscious mind or whatever I call it, intelligence, it’s there twenty-four hours a day. It doesn’t stop. It keeps going. It knows all. It sees all. And it’s in us and it’s up to me to tap into that.

That’s how I have sort of recovered my journey. My journey has been long and hard and finally I came to what people say is my inner child and all that. But when I say a child I literally mean that’s what came out today, that child that I’m keeping in me. And it’s here and here and now I’m letting it out. I feel like crying at times but then I know that it’s coming out.

Before when I told this story I would probably cry but now I’m at that stage where crying is there but it’s not coming out as much as it used to. So I’m on my way to healing. I’m trying to help other people. The only way that I know is to help other people to heal through the gifts that have been given by the Creator. That’s through love, kindness, generosity. That’s the laws that we have. They’re good, the seven laws that are there. I try and practice those.

Q. Merci beaucoup d'être venus aujourd'hui.

R. Je l'apprécie.

Q. Bien. Vous avez fait un très bon travail. C'était une belle interview. Merci beaucoup.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac