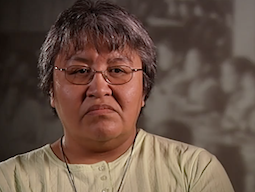

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

— Transcriber’s Note: Speaker is not identified by the Interviewer on the recording.

L'INTERVIEWEUR: Dites-moi dans quelle école vous êtes allé.

PERCY BALLANTYNE: Je suis allé au pensionnat indien de Birtle. Je ne sais pas trop exactement les années.

Q. You don’t remember how old you were?

R. J'étais juste un jeune enfant.

Q. Environ six?

R. Non. En fait, j'étais au début de mon adolescence; treize.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous à quoi ressemblait votre premier jour? Il y avait beaucoup de Dakota là-bas.

A. Yes. My first day was like —

Well, let’s go back to that first morning when I woke up at Residential School. I will never forget that. I had just come from a place, my environment, where it was nice and safe with family around. The family unit is around. The mom is around. The dad is around. Brothers and sisters are around. You sit outside your place and you are surrounded with the animals that are there, natural animals in the wild, the birds and you hear the birds singing, and that.

The next day all of a sudden I wake up in this strange place and I looked around, ‘oh, where am I?’ I panicked. I remember that feeling coming into my throat. I wanted to cry out. All of a sudden it dawned on me, here I am somewhere else. My mom is not around. My brothers and sisters are not around. My grandparents are not around. It was terrifying when I look around and see all these kids around you.

I heard the strangest sound coming from outside. It’s not a sound I was used to, the animals that are out there, the birds that are out there. It was different sounds, eh. I heard different types of birds like chickens clucking and cows mooing and pigs squealing. I mean, it’s a different environment. It’s a cultural shock. Wow, where am I?

My first instinct was I want to get out of here. I don’t belong here. I don’t belong here at all and it’s not the place for me. I looked around and there’s all these kids around me. The first thing I noticed was that kid that looked at me straight in the eye. Wow. This kid’s spirit is not in the right place, this kid’s spirit, you know, because when you look at somebody straight in the eye you could tell.

If you went to the jails or anything like that, if you look at the brothers and sisters out there in the eye you can tell their spirit is hurt. But it’s so sad at that age, at my age now when I think back, when I reverse, if I looked at you if you’re a prisoner I could tell that your spirit is hurt. Back then, when I look back now looking at those children that’s what really hurts me today, little kids, having the spirit of a prisoner. It stays with me. It never goes away.

And that feeling I had that morning of wanting to cry, as I’m sitting here it comes back, you know. I guess that tells me I have a lot more cleaning up to do. But I’ve come a long ways, I’ve come a long ways from when I was taken away from home.

My background, as I indicated earlier, I come from a loving family. I had my Kookum, I had my Mishum and my uncles and my aunties, my mom, my dad, my sisters, my brothers. That’s the environment that I know.

I come from the community of Grand Rapids. Grand Rapids to me at that time before we were disturbed from our little nest, our little safe nest there, I envisioned, I remember Grand Rapids as a nice calm lake, a nice calm lake, no wind blowing, not a ripple on the lake in the water, not even the leaves are moving. Everything is calm. I’m describing my family. That’s the way it was, eh.

Then one day somebody happened to throw a stone in the middle of the lake and created, bang, created that wave, that ripple, and we can still see the rippling effects today of that disturbance we had from Day One. Those were very terrifying moments when you see people coming to your place telling you that you’re going to leave your family, pretty soon you’re going to have to leave your family.

That’s just the way I guess our future was written for us.

Q. Pensez-vous que nous étions censés passer par tout cela?

A. I don’t believe that anybody had to go through what we had to go through, but in a way too we say that God works in mysterious ways. No, what we went through was horrifying. We found the root of the problems that exist today in our contemporary society.

I keep referring back to that nice calm lake and somebody threw a rock and started those rippling effects. Well today it’s still there. We see all kinds of social problems out there. We’re not the only ones that were affected by that issue of Residential Schools. The whole world’s society is affected by it. Nobody is excluded from the mistakes that past governments made.

In our way we have natural laws. I don’t like to use the word “Indian” because we’re not from India. We’re indigenous to this country where we are. I always tell the young people that it was God the Creator who put you here. Nobody else put you here. I don’t mean to sound biased or racist or anything like that to tell the rest of society that Columbus put them here. God the Creator put you here and this is your land, this is your country. Whatever happened to them they have to try to find that forgiveness so we can begin a new day, begin a new walk in life.

Q. Aviez-vous beaucoup d'amis à l'école?

A. I had a lot of friends. I made a lot of friends. I’m easy to get along with. I make friends fast, but at the same time I had enemies too, eh. I have a lot of friends out there (indicating). As a matter of fact, even though it’s watered down I learned the Ashinabe (ph.) language. I can speak it fluently because I grew up with the Ashinabe kids out there. I couldn’t speak Cree. I grew up with the chiefs that are out there. I grew up with them. We used to run, like five-thirty or six o’clock in the morning to do our exercise and runs and that. So, yes, I have a lot of friends from school.

But there’s the other side to it, too, eh, what happened with administration if you ran into trouble with the administration. The administration had their own bullies, too, eh, so at the same time I had to fight for my survival out there. I’m just a young boy from the north.

Q. Comment était-ce?

A. Well, it was terrifying at first when you’re surrounded by a bunch of strangers out there and their purpose is to try to intimidate you. I’m not easily intimidated by anybody so I always went for it. I went for it. I didn’t care how big or how small, you know. If you’re out there to pick on a young kid you gotta deal with me. They know about it, those people I’m talking about. But it wasn’t that we were bad. It was basically just survival, just trying to survive out there.

J'ai encore aujourd'hui des amis de cette époque. Nous nous entendons. Nous en parlons, vous savez, des mauvais moments et des bons moments que nous avons passés là-bas.

Q. Comment était la nourriture?

A. Well, from being up north you’re used to ducks, geese, traditional food, moose meat, muskrat, you name it. We were used to that. And then when you go down there you have to change. Everything changes. Even your diet changes. Everything can change. Your survival instincts change.

La nourriture elle-même, eh bien, je devais m'y habituer. J'ai dû m'y habituer.

Q. Quelle était la nourriture courante?

A. Porridge in the morning. Porridge in the morning, toast —

I don’t remember much about it. The only thing I remember about the Dining Room was the screams sometimes when you misbehave and that. That’s just where you got it, in the Dining Room.

Q. Devant tout le monde?

A. In front of everybody. Yeah, that’s in front of everybody. Yeah, you got it. It was very embarrassing and humiliating for some poor children out there.

But so vivid in my mind is I never laughed at anybody. As a matter of fact when I heard those screams it got me angry. I wanted to go and protect those kids, eh. It’s a natural instinct for you to protect. When that happened to my little brother I went nuts. I broke a law. Let’s put it that way, just to back up my brother. I’m just going a little bit ahead here, eh.

Je suis allé à l'école avec mon frère. Il est décédé l'année dernière, il n'y a même pas un an. Il est décédé et je suis allé à l'école avec lui là-bas.

Q. Vous surveilliez beaucoup son dos?

R. Oui. Beaucoup. Je l'ai protégé.

Q. You probably weren’t as lonely, then. You missed your grandparents and your mom and dad but you had your brother there.

A. I had a responsibility now when my brother came there. Actually, he didn’t even know that I was there. I didn’t even know that he was coming there. One day I was in the Study Hall and the principal came and got me. He says, “Ballantyne, go out to the hallway.” I thought I had done something wrong. The only time you went to the hallway was if you had to stand in the hallway. He says, “Go to the hall.” And I stood out there and I seen this little boy come walking down the hallway. He looked up at me and I just —

That’s my brother. I just went running up to him. “Hey”, I says. I grabbed him. I hugged him. My little brother. The happiness, the expression on his face, I still remember that expression on his face. Hey, I’m not alone. My brother is here. So I just embraced him, you know. I just took him under my wing and that.

He was skiing there for a while at the time I was there. We were good athletes, too. That’s one thing about Residential School. We were very athletic: sports, recreation and stuff like that. I wouldn’t like to say it was totally 100% bad because you did meet good friends there, you know, that lasted a lifetime. You got to know people and you got to meet other people from outside, people that came to visit the other kids there. I met some parents out there that I met later on with my friends.

I would like to forget —

This person was speaking and —

I would like to go on with life and put the hurts aside, just keep on moving ahead because it can’t go on like this. It just can’t go on like this. There is a process of reconciliation with Canada, First Nations and that’s a pretty big word. How could you reconcile with somebody that hurt you? How could you go up to them and say “I forgive you” after you have been through the windmill a hundred times, a thousand times over?

But this culture, culturally speaking, we are a very kind People. I want people to understand that, to know that, who we really are, you know, not the way they perceive us to be. Because for too long we’ve been told what to do, how to act, when to say things, when to speak up, who you should be, you know. The time is here now to tell the truth, to really tell the truth and to tell society who we really are.

I’m not an Indian. I never will be an Indian. As a matter of fact it’s just like calling a Black man that bad word. The Black People don’t like to be called that word. And it’s beginning to be like that with us People. Don’t call me an Indian. I’m not an Indian first of all, and number one, I’m a (speaking Native language) —

— means a person who speaks Cree. (Speaking native language) We’re the Cree People. (Speaking Native language) We’re the People from the north in the medicine wheel. We sit in the north. That’s who we are. That’s the real identity part of us (speaking Native language). That’s who we are.

Q. Avez-vous déjà eu honte de l'être?

A. I could never remember being ashamed of the way I was raised. Ever since I was a little boy my grandma and my mom were very good teachers, and my grandpa told me to never never ever deny who I was. “This is the way the Creator made you. That’s who you are”, he says. “I’ve got a message for you, young man,” he told me. “My Elders, before you were born”, he says “the Creator already decided who you are going to be.” “In the spirit world”, he told me, “that they already picked you. The Creator only wanted the strongest spirits there is to come down and live in this world as who we are — let’s use the term “Indian” — to be Indian because he knew that’s the hardest road to travel, to walk in this world.

I tell the young people to be proud of who you are, you know, you’re strong. You’re a very strong person. You’re a special person. So the Creator made you that way. He wanted you here for a purpose to get that message for him, to really tell them who you really are, to tell society who you really are not the way people expect you to be.

No, I was never ashamed to be because my mom told me in very strong words she told me, and my grandparents. If you deny who you are maybe God the Creator will deny you. He’s not going to believe you if you tell him I’m English and French, and that, when in fact you’re Cree. He’s going to deny you. That really stuck in my mind. Wow.

So from then on I always always was proud of who I was, the way my Elders, my grandparents, my mom, those people around me taught me about my identity. They didn’t solely put me here in North America but they connected me to God in the spirit the way he made me, the way he wanted me to live, to walk in this world as a Cree. That’s who I am. I’m very proud of who I am.

Q. Vous êtes-vous déjà retrouvé aux prises avec cela dans les pensionnats indiens?

A. In Cree? Being Cree? Like I said, I’m not biased or anything like that but yes, I did. The way administration works sometimes when you get into trouble with them, sometimes the Northern children were abused from the orders of administration and it was the Southern kids that done that. This is where that rift —

Q. Vous avez été distingué?

A. We were singled out, yeah. But when you put your foot forward and you say “you’re not taking me, c’mon, let’s go, let’s go, let’s get it over with, if you beat me, well, that’s fine.” “If I beat you leave me alone.” So that’s the way it was. No, I never did that, struggle with anything like that. Just keep on walking in life, like I was conditioned already with love, with care, with wise teachings from my Elders in the community. Those are the ones that really carried me through in life to be able to make the right choices in life, the right decisions.

Yeah, you make mistakes along the way. But I guess part of colonization is to control. We were controlled and conditioned, changed to act in a certain way. That’s what the Residential Schools —

They perceived them as political laboratories where they done their political experiments to change —

To change an eagle to act like a crow, that type of thing. It didn’t work. That political experiment was zilch. It just went haywire. It did not work and it will never work. You can never change an eagle to act like a crow.

Q. Avez-vous dû laisser votre frère là-bas?

R. J'ai dû laisser mon frère là-bas.

J'allais laisser ça vers la fin.

Quand j'étais là-bas, j'ai essayé de m'enfuir.

I took these two young Dene boys under my wing. They were —

I’ll use the name. They were the Toms (ph.) from Tadoule Lake. They were the twins, twin boys. But they were really —

Comme les enfants s'en prennent à eux et ils ont commencé à pleurer et tout ça.

Q. Ils étaient dénés?

A. Dene. Ils les appelaient des mangeurs de viande crue et des trucs comme ça, hein. C'était très très dur de leur part.

They did survive. One of them passed away. I just seen one last week here in Thompson. He was really happy to see me. Ballantyne, Ballantyne! I said, “Yeah.” “Remember me?” I said, “How could I forget you?” “See my nose?” “That’s because of you.” (Laughter)

A part ça, il y avait des abus là-bas.

Q. Abus physique?

A. Physical, sexual and emotional abuse. I don’t like to hear children cry. My heart just melts. To hear people crying does something to me.

Q. Vous avez beaucoup entendu pleurer?

A. Ouais.

Q. Avez-vous vu beaucoup de choses?

R. Eh bien, quand vous voyez des choses et que vous êtes exposé à des choses, cela reste dans votre esprit. Au fond de votre esprit, vous savez ce qui est bien et ce qui ne va pas et vous savez ce que vous voyez là-bas est faux. Mais on vous dit de ne rien dire ou bien, vous savez, c'est ce qui va se passer. Il y avait des menaces si vous dites quelque chose.

Certains enfants ne sont jamais rentrés chez eux pour des pauses. Ce genre de choses, ce genre d'abus.

Q. Êtes-vous rentré chez vous?

R. Je dois rentrer chez moi. Ouais. Mais je me suis enfui aussi plusieurs fois.

Q. Vous vous êtes fait prendre?

R. Je me suis fait prendre. Heureusement je me suis fait prendre. Dieu merci, je me suis fait prendre, moi et ces deux garçons dénés que nous avons attrapés. Sinon, nous serions devenus une statistique. Trois autres enfants se sont enfuis de l'école et ils sont morts de froid. Nous avons presque gelé.

Q. Que s'est-il passé?

A. Well, we ran away and we just hopped on a train and the train stopped and we hopped out and we just started walking we didn’t know where. We didn’t know where we were. All we could see was just fields and fields. No trees. It was cold. At least we were saying if we were out up north somewhere we could make a fire. But there were no trees out there.

Q. Portiez-vous des vêtements d'hiver?

A. Just very skimpy jackets. I wore my slippers. That’s how desperate we were to get out from there. I wanted to try to get my brother to come with us but at the same time I wanted to leave him behind because I knew it was going to be a hard journey if we made it. My plan was to tell my mom and dad what was happening there.

Q. Leur avez-vous jamais dit?

A. I told them. But that generation of parents was scared of authorities. They were scared of Indian Agents. They were scared of police. They were even scared of Ministers, and that. They had a lot of power and authority over our lives, every aspect of our lives, that’s what they had.

Q. Vos parents ont-ils essayé de vous garder à la maison?

A. I don’t know. That’s something I’m dealing with today. There’s a gap there. Like you feel abandoned, you know, that issue still. But I made peace with my mother before she passed away. I made peace with my dad before he passed away, too. I was one of those kids that was conditioned to stand up for who you are, the first born of the family, so I always had to stand up for what I believe in, the way I was raised in the faith, and that.

Q. Combien de frères et sœurs avez-vous?

A. There’s fifteen of us.

Q. Sont-ils tous partis?

A. Save one. Fourteen went. The baby didn’t go, the baby of the family. My mom didn’t want to let him go, her baby.

Q. Où sont allés les autres enfants?

A. They went to Dauphin. I don’t know —

Ma famille, j'ai juste perdu le contact avec ma famille après ça. J'ai décollé après ça.

Towards the conclusion of my school years as I stated earlier my brother, the late Wesley Ballantyne was a very small boy and I didn’t know and he didn’t tell me that he was getting beaten up by the supervisors, a male supervisor.

Q. Tout le temps?

A. A male supervisor, a Mister and Mrs. I won’t give the name because of something pending out there. But he was getting beaten up and then one day we were in the Study Room and I heard a commotion and I heard a familiar voice crying out for help. There’s my brother. I got there and he was doing something to him and I lost it.

Q. L'ont-ils battu?

R. Plus que ça.

Q. Plus d'un d'entre eux?

A. More than beating. Like I said, I don’t want to say anything because it’s going to come out. But I lost it.

Q. Ils l'agressaient sexuellement?

A. Toutes sortes d'abus, oui.

Q. Quel âge avait-il à l'époque?

R. Il devait avoir environ douze ans, je suppose.

Q. Oh, il était encore un bébé. Qu'est-ce que tu as fait?

A. Like I said, I lost it. That instinct to defend. I grabbed a knife. I didn’t hurt anybody. It was more like to scare them off. Kids still talk about that today at Birtle. They knew I wasn’t there to hurt anybody. I took a knife to them. I didn’t stab anybody. I didn’t hurt anybody. It was just to scare them off. That was my intent. That was my intent.

Mais je suppose que je l'avais eu jusqu'ici (indiquant) à ce moment-là parce que chaque fois que j'avais des ennuis, je devais blanchir la porcherie. C'était ma punition, et pour laver les escaliers, trois volées d'escaliers avec une brosse à dents.

Q. Just one second. We’re going to change the tape.

— End of Part 1

Q. Très bien. Continue. Parlez de ce dont vous voulez parler. D'accord? Parce que vous devez savoir que vous le laisserez ici.

R. Mes camarades d'école là-bas, beaucoup d'entre eux sont décédés et ça fait vraiment mal aujourd'hui de savoir qu'ils sont morts de cette façon. Moi sachant ce qu'ils transportaient, même au fil des ans si nous nous rencontrions dans les rues de Winnipeg, cette fraternité était là. Mais sachant qu'ils sont morts comme ça, ces enfants ont été vraiment maltraités.

One guy from Way-Way, the other guy was from Portage, that area. Those guys were really —

I don’t know if I should say it. Maybe it will make —

But psychologically it affects you, it affects you, being exposed to abuse. Like it really blows your mind away to be put into the care of people, your parents expecting that you are going to be well taken care of and here’s these things happening to children. Good lord, man.

We’ve been here for millennium after millennium, thousands and thousands of years we’ve been here. And then in 1492 people come over here and that’s only half a millennium and they’ve done a lot to us. Crime. A crime has been committed against our people and why is that allowed? Why is that being allowed to let those things happen to little Indian children?

Si la société blanche savait un jour ce qui s'est passé, la vérité sur ce qui s'est réellement passé là-dedans, et s'ils pouvaient se mettre à la place de nos parents et échanger leurs enfants contre nous, les laisser s'asseoir là où nous étions, je me demande comment serait la société . Quel genre de tollé se produirait?

Here we are trying to get the truth out there. We’re meeting obstacles left and right. When is the hurt going to stop? Because right now people are hurting right now.

Right now I’m working with Manitoba Keewatin (something). I’m the Regional Coordinator —

I have clients out there, too, Residential School survivors. We talk a lot. We have Healing Circles, Talking Circles, and that. To go into the world of an Elder, to go into the world of an Elder, that Elder is taking you back to when they were that high (indicating), you know, it’s an honour to be invited to go on that journey, although it’s hard. It tears me apart, just tears me apart. But at the same time it makes me strong as a warrior. I would die for these people if it came down to it. I would be the first one there for our People. People know that about me that I will protect them because I don’t want anybody to go through those types of things that we went through. To be ripped apart from the embrace of your mom, the loving embrace of your mother, from your dad, from your whole family, you know, that’s a crime itself. We’ve been robbed of our life. There’s no other word for it. We’ve been robbed of our childhood, robbed of our innocence, robbed of our whole life itself. And on top of that, robbed of our country, lands and resources. When is it going to end?

Our problems today are attributed to the treatment and the management of lives of our People. We have been mismanaged. I don’t know who gave them that authority to come out here and manage lives. We sure as heck didn’t. But the way you manage lives that’s the way you are actually laying the foundations of your future.

This is not our future. This is not our society. This is White society. This is not First Nations society. This is not our life. That’s not our life. Gang life is not our life. Wife-beating is not our life. All kinds of things that are happening, that’s not us. That’s not our life, you know.

Nous savons qui nous sommes. Nous savons que notre système de valeurs culturelles est connecté à Dieu le Créateur et que le système de valeurs culturelles sont ceux que nous vivons quotidiennement pour aimer, pour nous soucier, pour être honnête, pour coopérer, toutes ces choses, c'est la sagesse directe et les lois directement du Créateur pour nous.

Also our medicine wheels and the teachings of our medicine wheels. It is told that every nation in every four corners of the world have their medicine wheel and they abandoned them for the sake of whatever. I’ve been told that our people are the only ones that kept the teachings of the medicine wheel. And we have the answers. We have the answers to these problems, the woes that’s out there, the problems that are out there.

I’ve also been told that the lighting of the seven-generation fire is here already and that Indian people are the ones that are going to lead in that area. Whatever word, whatever term you want to use, whether it to be healing or to bring people together, I’ve been told that our People are going to be the ones that are going to start that circle and start holding hands, regardless of what we went through.

Q. Notre heure est maintenant.

R. Notre temps est venu. Ouais.

Q. En retournant au pensionnat, vous rappelez-vous quel âge vous aviez lorsque vous êtes parti?

A. Well, I have a history. I have a history. I didn’t go directly. I was part of the 60’s school. Okay?

Q. So you went from there to…?

A. Aux pensionnats indiens. Ouais. Ouais. J'étais loin de mes parents pendant longtemps. J'ai perdu contact avec eux.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous?

A. I was probably about twelve years old, I guess, eleven or twelve, around that area. Maybe twelve or thirteen. Like, that’s just something that flew by. It’s something I don’t want to remember. It hurts too much. I want to forget about it. But I was just a young boy.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous avez été adopté?

A. Environ onze ou douze ans.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous êtes allé au pensionnat?

A. Environ dans mon adolescence; treize, quatorze, quinze.

Q. Donc, vous étiez d'abord absent et ensuite vous êtes allé au pensionnat?

A. Ouais.

Q. Oh. Wow. If there were a list of terrible things you can do to a person you have managed to strike all of them on that list. That’s terrible.

Alors, où avez-vous été élevé?

A. I was raised at Kamarno, Manitoba, close by Toulon Residential School. As a matter of fact I did hear about Toulon Residential School a few times in the foster home because by that time I was very hard to manage already. I was so lonely. I wanted to come home so I ran away. That’s how I ended up in Residential School. I got picked up again. I made it to my Reserve but they shipped me to a Residential School.

That’s another —

That’s one horrific story. I have nothing good to say about Residential Schools.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous de la famille avec laquelle vous viviez?

A. Ouais. Dans la famille d'accueil. Oui, je m'en souviens.

Q. Vous ont-ils été gentils?

R. Oui, ils étaient gentils avec moi. Ils ont été très bons pour moi, ma mère adoptive et mon père adoptif. Sauf que ma petite sœur adoptive me faisait des grimaces juste de l'autre côté de la table, vous savez. (Rires) Elle plissait le nez comme si je sentais, ou quelque chose comme ça. Alors j'avais l'habitude de lui raconter ça, et ça. Ensuite, mes parents l'envoyaient dans sa chambre et je restais en bas le reste de la journée.

Q. Les voyez-vous encore?

R. Oui, je les ai vus. Mes parents adoptifs sont partis maintenant.

Q. Et la sœur?

R. Les sœurs sont toujours en vie.

Q. Leur parlez-vous toujours?

A. Oh, I talk to them once in a while. I still keep in touch. They’re just like —

They may be White but they are like my brothers and my sisters. I still keep in touch with them. There’s that deep respect for one another. It’s not going to go away.

Q. Vous les aimez?

A. Of course. That’s the only love I met when I needed somebody to understand me as a child. My foster parents were there. They understood me better. They bought me a horse. They bought me this. They bought me that. I grew up with that horse. It was just like a dog. I trained it like a dog. When I whistled it would come running. When I talked to it it done things for me.

The abilities that we have as People, it’s amazing. You can do anything.

Q. What was your horse’s name?

A. King. I called him “king”. I don’t know why. I should have called him “chief” instead. (Laughter)

Q. C'était un peu déroutant. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous avez quitté cet endroit?

A. It’s in my early teens. I would say about twelve or thirteen. I can’t remember much.

Q. Combien de temps êtes-vous resté avec eux?

A. I don’t know. It was just a phase. See, my background —

That’s when hydro came to Grand Rapids. All of a sudden, bang —

Q. Est-ce à ce moment-là qu'ils ont construit l'autoroute 6 et que toutes ces choses terribles ont commencé à se produire?

R. Oui. Ouais.

Q. Les gens avaient accès à l'alcool?

R. Oui, de l'alcool. Tout d'un coup, nos parents étaient des agresseurs. C'étaient des buveurs. Sauf ma mère, elle n'a jamais bu jusque-là. Elle ne l'a jamais fait. Mais mon père, il est passé du jour au lendemain d'un père aimant à un agresseur, du jour au lendemain.

Q. Est-ce qu'ils sont allés au pensionnat?

R. Ma grand-mère l'a fait.

Q. Votre grand-mère l'a fait?

A. My grandma and my auntie did, but my dad didn’t.

Q. Et votre maman?

A. My mom didn’t.

Q. Non.

A. No. But my dad —

Par exemple, mon père s'est joint à la GRC et est devenu l'un des premiers flics de la bande, puis il est allé à Regina.

Q. Mon père aussi.

A. He went to Regina and he turned abusive overnight. I lost my dad. I lost my dad that time. Wow. When he come back from Regina he was never the same again. Where’s my dad? Where’s my daddy? I want my dad. He was a different guy. He turned like that. I don’t know. It’s really confusing when you see your daddy turn. It sends very bad messages to you, confusing messages, to live in that state of abuse.

And then from there when you go to an institution you see that abuse it just conditions you, you know. With the choices I made in my life, boy, I have to admit I was abusive too, once upon a time. But I learned along the way that’s not right. I abused myself. I abused everybody. I lived out on the streets.

Q. Vous étiez physiquement violent?

R. Oui, physiquement. Je me bats beaucoup et bois beaucoup et des trucs comme ça. C'était une véritable guerre contre le monde, vous savez.

But had we been managed properly Canada would be one of the smartest countries in the world because Indian People are smart, very smart people. The reason I know this as a mentor living up north and that, there’s a different lifestyle, disparities between north and south. There’s economic disparities.

Dans le nord, vous devez apprendre les habitudes des animaux. Il faut chasser, pêcher ou piéger, donc il faut connaître les comportements des petits animaux. Si vous allez chasser l'orignal, vous devez étudier les orignaux, leurs comportements et tout ce qui les concerne, ce qu'ils mangent, vous savez, comment ils vivent là-bas. Donc, quand vous partez à la chasse, vous devez penser et sortir intelligemment cet orignal, il faut donc beaucoup d'intelligence pour sortir un animal très intelligent. Même les loups, comme les loups là-bas, ils représentent la communauté. Ils représentent le gouvernement. Ils représentent tous les aspects de cette vie là-bas.

Q. Chassez-vous encore?

A. Not lately. I haven’t. I gave that up quite some time ago

Q. But you’re running?

A. I’m running. I still run quite a bit.

When I was up in the Yukon in the eighties I hunted quite a bit up there. There’s a lot of moose out there.

I just love to run. Let’s put it that way. Running and recreation —

I have a boy out there. His name is Marlin Ballantyne. I have a Society. We’re called the Lance L-a-n-c-e Runners Society. This is my healing, too, part of my healing. And also to get the young people together, to get the young people to capture their energy, to capture that energy and to use it positively. As long as you get them to see the picture and tell them, “Hey, listen, this is what you’re here for. The run for this year is for Residential School effects and affects”. We done that in 2005. We ran from Gilliam to the Legislative Building in Manitoba and we ran to Ottawa. It was the young people that made it happen. If it hadn’t been for them it would have never happened.

When they ran to Ottawa and we told them the message, I told them the Lance Runners are the messengers of peace, love, hope, understanding, messengers of our People to society that we’re not those savages, we’re not barbaric, we’re not as they taught us in school curriculums. You go out there and be an ambassador of the Cree People, of our People.

Q. Courez-vous à nouveau cette année?

A. We’re doing a run from Moosonee, the Cree Nation of Ontario, to Grand Rapids. We’re hosting the Cree Nation Gathering this year at (something) Cree Nation.

Q. Over time —

A. Yeah. I started those runs. Back in 1996 was the first Unity Run we organized involving other Cree Nations and Communities from across the country. Other than that the original ones were from Grand Rapids Cree Nation. I only had ten runners, ten young boys. We ran over here for two summers in a row. Nobody noticed us. We weren’t looking for that. We weren’t looking for a pat on the back or anything like that. It was just something for the young kids to do and they just loved it. They just loved to run. There’s something about running that is freedom, the wind and just being out there, you and the land.

We ran over here and in 1996 we were joined by Alberta and then it escalated from there. It grew. So we’re national but we’re fragmented. We need one major group, one right across Canada. So we will get there eventually.

Q. Où formez-vous vos garçons?

A. It’s entirely up to them. We are just in the community, just what these boys are. They are both young boys.

Q. Courez-vous toujours activement?

A. Yes. I live up in Thompson. I haven’t started training yet! But I’m going to. I do a lot of walking.

Q. Quel âge avez-vous maintenant?

A. I’m fifty-four years old.

Q. Génial. Y at-il autre chose que vous voudriez ajouter?

R. Juste pour conclure au sujet de mon frère qui a été victime des abus et ensuite quelque chose m'est arrivé et j'ai senti que c'était la bonne chose à faire et je les ai poursuivis. Je le défendais juste, hein.

But then after that I ran away. I ran down the hill but I knew the police were coming. Here is my chance to escape. I’ll go to the police. I waited for the police down the hill. Before I had put that knife right on the ground, that’s where I left it, and the police came by and asked my name and I told him right there. As soon as I pointed at that knife he kicked me right here (indicating) and arrested me. They took me to Brandon, Brandon Jail. I was just a young boy and I stayed there for one month.

My mom and dad didn’t even know where I was. Just one day I appeared at their door at three o’clock in the morning. I had to hitch hike back to Grand Rapids. That’s the neglect that the system put on us.

Jail, that’s another area. I just don’t like that justice system out there. There’s no such thing as justice. The only thing justice about it, they discriminate against “just us”. That’s about it.

Q. Justice or “just us”?

A. Yeah. Justice —

Before you can know what “just us” is you have to know that the injustices are.

That’s about all I have to say. I don’t have a lot to say on that neglect, a few things out there because of court proceedings, I guess.

Q. Êtes-vous au tribunal maintenant?

A. Not yet. Not yet. But I may be called as a witness. Those young boys I’m talking about, I don’t want to say it. It has to do with animals. I will leave it at that.

Q. That’s sad.

R. C'est vrai.

Q. Ils faisaient faire quelque chose aux animaux pour les garçons?

A. Vice versa.

One of them is a darn good artist, a very terrific artist. And if he ever needs me he contacted me already, I’m going to go there for him. And the other guy he already passed away. You know, these are such tremendous individual human beings. They are so intelligent. They are so smart. And yet you wouldn’t tell if you were looking at them. You can’t tell. Once you start taking them apart, man, this guy is this and that, that guy is this and that. You wouldn’t even think these guys survived what they went through. You would think they are whole people, real smart people. That’s the sad part. If only we could be whole holistically; mind, body and spirit, connected together as a braid, the way we braid our hair, eh.

Je pense que ces jours arrivent bientôt.

Q. Oh oui.

A. The fire has been lit already and we’re here. We’re working, throwing in a log here to make it brighter, as it has been foretold. Those things are happening. That’s why you’re here. That’s why I’m here and all our People that are out there. We’re on that healing journey.

Like I said earlier, I would like to leave this behind and start a new life because a new generation is coming out there. We’re getting older. I’m getting older and my kids are going to have children and a new generation is coming up. I don’t want to leave them this legacy. I want them to see who I am today, so that my children and my grandchildren in the future will say my grandpa went through an uneven journey and he survived Residential Schools. He survived what was thrown at him. I want them to remember that story that I told about the Creator making them who they are, as spirits, and he only picked the strongest spirits in heaven to come down as Indians and to walk this world as Indians.

He’s going to welcome us that way if we maintain our pride, our dignity, our language and everything. I know these things.

I’m also a sun dancer. I believe in that. I believe in a lot of things that come to me in a dream. The Unity Run came to me in a dream. The Creator used geese and wolves on that Unity Run. A lot of people claim it’s theirs today. No. You don’t steal another man’s medicine bag and expect it to work. It’s happening. That journey is beginning, that healing journey.

I say that to the young people. I send my voice into the future with you, the message you are going to carry from this generation is we’re not going to allow that to happen again. That’s my voice. That’s your voice, your grandparents’ voice. The ones that didn’t make it home, that’s their voice. I say, “Carry it into the future. Run. Run with it. Tell them.”

Merci.

Q. M’gwich.

R. Oui.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac