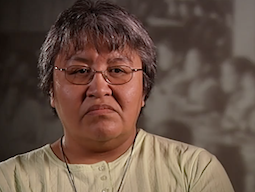

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

L'INTERVIEWEUR : Pouvez-vous dire et épeler votre nom ?

PATRICIA LEWIS : Patricia Lewis ; Patricia Lewis.

Q. D'accord. Et d'où viens tu?

Première nation A. Eskasoni.

Q. Et quelle école avez-vous fréquentée?

R. J'ai fréquenté le pensionnat de Shube, Shubenacadie. J'ai fréquenté l'école de jour indienne un an à Eskasoni.

Q. C'était en quelle année ?

A. I don’t really remember.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous de votre âge ? C'était un externat ?

R. Je pense que j'avais environ onze ans à l'époque.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous êtes allé à Shubenacadie ?

A. I believe I was 6, going on 7. The year was 1957. I remember, because that summer, that fall actually, my older sisters Maureen, Shirley and Miranda, they prepared us. They said we were going to “Resi”. And we gotta cut your hair because they are going to cut it anyway. We all had to line up and they cut our hair, below our ears.

Q. Vos sœurs l'ont fait pour vous ?

R. Ils l'ont fait avant notre départ. Nous avions couru tout l'été, vous savez, avec nos cheveux longs tout ce temps. Alors je me souviens que nous étions plus ou moins prêts à partir.

Q. Vous ont-ils préparé autrement ? Ont-ils parlé de ce à quoi s'attendre?

A. Not that I can really recall. All I basically remember is the hair cut. That was most significant. But I think maybe Miranda might have told us something like if you’re bad they are going to beat you with a stick, or something like that.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous de votre premier jour à l'école ?

R. Je me souviens quand nous étions en route. Nous avons pris le train. J'étais assez excité, je pense, à l'idée d'y aller. J'étais avec mes sœurs et mes frères et j'en connaissais beaucoup qui y allaient. Cela semblait amusant sur le chemin.

But we arrived there and I remember the first thing one of the Nuns there said when we were introduced. My older sisters there said, “This is my younger sister and younger brother.” How many of us?—One, two. No, there was just me, I think, at that time. Because I don’t think Marilyn and my other brother Russell went there then. It was me and Harriet and Annette. They had already known the other sisters there, the older one. But they didn’t really know Harriet, I think. No, they didn’t know me. I was the only one. I remember now. I was the only one. And the Nun says, “Oh, another one of you!” She says, “Oh, another one of you.”

My older sister there got defensive and said, “Yeah, there’s more of us at home, too.” The Nun was pretty disgusted, it seemed.

Q. Combien de frères et sœurs avez-vous?

A. Well, there were originally eleven girls and 5 boys in the family. But we’re down to I think it’s 3 brothers and ten girls now.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous d'autre chose de ce premier jour?

A. Well, it was pretty bad I would say. We had to line up and they stripped us. They made us take off everything. We had to stand there and they powdered us with this white powder, you know. I didn’t know what it was but we were all white anyway. We were white all over, covered in this powder. I learned later that it was DET and that we were being de-liced. We never had bugs, you know. They made us take a bath and put us in these little uniform things. Everyone ended up having a number.

I don’t remember what my first number was at that time. But I remember the clothes we got, the clothes and shoes that we got, the Nuns told us we had to take care of these because these are all you’re going to get. And if you lose anything you’re going to get in trouble.

Q. Alors, qu'en est-il d'une journée type. A quelle heure deviez-vous vous réveiller et qu'avez-vous mangé au petit-déjeuner et ce genre de choses ?

Pouvez-vous nous présenter une journée type ?

A. Oh, a typical day, for me was pretty bad in the beginning. The Sisters wake you up either with a bell or they clap their hands real loud. Get up! Get up! It’s 6:30. I would say it was 6:30 in the morning. We would have to be up. Everyone made their beds. I was too young to do any of that. But the first thing every day was —

I was a bed wetter, so I wet the bed every day. So every day, every morning I would wake up and I would get a beating. The first day I was there, the first night I was there I was warned. I remember I was warned. If you wet the bed they are going to punish you. Well, I can’t help that. I’m only a kid. But I wet the bed that first night and when I got up the next morning I didn’t get a beating. I was warned. But the second time I got a strapping. They used a big belt. For a little kid it was a big belt.

That was the start of a typical day for me, on a daily basis, the beatings. It was usually ten whacks with the belt on the butt. A lot of times I would be made to —

Before I even had breakfast, or I wouldn’t get breakfast because of it, or a late breakfast, but I would always have to bring my sheets down and hold them up in the air in the cafeteria.

Q. Devant tous les autres étudiants ?

A. In front of all the other kids, yeah. But I wasn’t the only one. So I didn’t feel too bad about it really. It was the beatings I think that were more hurtful than that.

So a typical day —

It varied for me. Being so young and all, being a bed wetter, sometimes I would have to wash the sheets myself in the tub down there after I took a bath, or before I even took a bath, and hang them out outside. I had to go out. It didn’t matter what type of weather it was. They had to go outside.

After the breakfast thing, holding them up in the air, and either I would get breakfast or I wouldn’t.

Q. Que diraient-ils lorsque vous deviez tenir ces draps ? Que diraient-ils au reste des élèves ?

R. Ils essayaient de nous faire honte. Ils nous ont fait honte, tu sais. Regarde-les. Ce sont les mouilleurs de lit. Ce sont eux qui mouillent leurs lits. Et quiconque ici mouille son lit, voilà ce qui lui arrive. C'est ce qui va vous arriver si vous mouillez votre lit.

Je me souviens d'un jeune garçon là-bas, Lester Sylliboy, il était l'un d'eux aussi, du côté des garçons. Je crois qu'ils l'ont battu une fois avec la sangle, juste là à la cafétéria devant tout le monde.

Q. Qu'en est-il de la nourriture. Comment c'était ?

A. To me the food wasn’t so bad. They had porridge in the morning. We got our porridge. We had bread. We had juice and milk, sometimes, juice and milk. The milk was supposed to go in the porridge. If they had oatmeal —

Parfois, ils avaient des céréales de la rivière Rouge avec toutes sortes de choses, je pense que c'est venu plus tard. Mais c'était généralement de la crème de blé ou des flocons d'avoine. Ils avaient toujours des grumeaux dedans. Ils avaient toujours des grumeaux en eux.

Sundays were supposed to be special because I believe we got an egg, a boiled egg and toast then, and juice. But a lot of the girls and guys I guess they didn’t like the porridge because it had lumps in it. Me, I didn’t care. I was always one for eating anything and everything, you know.

Q. Avez-vous eu assez de nourriture?

A. I can’t say I starved. I went hungry a lot of times because of the punishments I went through, but I can’t say I starved. I know a lot of the girls —

You couldn’t leave anything on your plate and a lot of the girls, they didn’t like the lumps. Well, I didn’t care if I had lumps in my porridge or not. Give me your lumps. I’ll take your lumps. I ate their lumps so they wouldn’t get in trouble. Me, like I said, I didn’t care.

Je repense à ça. C'était marrant. J'ai sauvé beaucoup de vies, je pense, en mangeant leurs morceaux. (Rire)

Q. Prenant leurs morceaux.

R. Oui, j'ai pris leurs morceaux. Et à bien des égards, vraiment.

Q. Qu'en est-il de l'éducation que vous avez reçue ? Pensiez-vous que c'était une bonne éducation?

R. J'ai beaucoup appris. J'étais intelligent au début alors j'ai tout ramassé. Je savais déjà lire et écrire mon nom et compter jusqu'à cent. Je connaissais toutes mes couleurs, avant même d'y aller.

Je pense que j'étais à la maternelle pendant une semaine, même pas, et ils m'ont mis en première année. Je savais tout là-bas et ils m'ont mis en deuxième année. Ils m'ont gardé en deuxième année. Je suis donc passé de zéro à 2 au cours de cette première année, je crois.

Q. Jusqu'à quelle note est-il allé?

A. Huit à l'époque, 8e année.

Q. Et est-ce que quelqu'un a dépassé la 8e année? Y avait-il un lycée dans le quartier ?

R. Pas là. Pas là à ma connaissance.

Q. Était-ce la fin ?

R. C'était la fin, je crois, pour l'éducation. C'était la 8e année.

Q. Donc personne n'est allé au lycée après ça ?

A. No. Grade 8 there and you were outta there. Or you just didn’t go back because of a parent wanting you back, or something going on or whatever. I don’t remember.

Q. En quelle année avez-vous fini là-bas?

R. 1966. J'y étais jusqu'en 1966.

Q. Y a-t-il d'autres expériences que vous pouvez partager avec nous aujourd'hui au sujet des pensionnats indiens?

A. Well, we still didn’t finish the typical day for me. I was still in the morning.

Q. Okay. Let’s finish it.

R. Après la punition, après les draps et tout ça, je devais me préparer comme les autres, vous savez, pour l'école. Nous avions les uniformes et nous faisions la queue et tout le monde allait dans sa classe.

Et puis déjeuner.

Q. Aviez-vous aussi des tâches ménagères le matin ?

A. Well, after the breakfast thing, they would usually assign different ones to do different things. I don’t remember doing anything really the first year I was there. There couldn’t have been too much I was doing. But after I used to sweep the stairs down, wash the stairs down, from the third floor all the way down to the basement area. I did that.

I worked in the dorm, I think, one side of it. That’s doing all of the beds, under the beds, dusting and this and that. I worked in the Rec Room one other year, dusting everything, taking toys down, and that. Hallways, down the stairs, washing them, sweeping and dusting the banisters, everything.

J'ai travaillé au deuxième étage un an et les escaliers qui descendaient, qui menaient de la cuisine. J'avais l'habitude de faire la salle à manger et de dépoussiérer les couloirs. Je pense que j'ai travaillé à l'étage une autre année. Et dans la chapelle faire tous les bancs et polir et balayer et frotter.

Everything was done on your knees. A lot of stuff was done on your knees. I got bad knees now from that. I can’t be on my knees. Every time I get down on my knees for any reason whatsoever it hurts, you know.

Q. Les religieuses étaient-elles vos professeurs ?

A. Yeah. They were all our teachers. If they wanted to make a point, if they caught you doing something you’re not supposed to be doing, they had their wooden rulers and their little pointers and you would get rapped on the knuckles or rapped on the head, or poked in the chest or the throat, wherever they decided to poke you, or hit you.

Il y avait beaucoup d'abus là-bas, sur une base quotidienne. Beaucoup d'élèves, pas seulement moi, ont subi de nombreux abus physiques et psychologiques.

Q. Pouvez-vous parler de certains abus émotionnels ?

A. Emotional was —

I remember Sister Gilberte (sp?) used to get really pissed off at us when somebody lost a handkerchief or a sock, you know. We had inspections for underwear, dirty underwear for that matter. “If your underwear is dirty you’re going to get punished.”

Elle nous traitait beaucoup de sauvages et de païens. Je n'ai jamais su ce que c'était. Je n'ai jamais su ce qu'était un sauvage et je n'ai jamais su ce qu'était un païen. Je n'ai jamais mis beaucoup de ces trucs ensemble jusqu'à beaucoup plus tard dans la vie. C'était vers 1980, j'ai commencé à assembler des trucs.

Q. Étiez-vous en mesure de pratiquer l'une de vos propres traditions à la maison avant d'aller au pensionnat pendant les premières années?

A. Well myself personally I wasn’t born on the Reserve. I was born in Toronto. My mother and father were in Toronto and my mother left a few of us here and there along the way, so I was one of the ones that was born away from the Reserve. I ended up getting left there, for whatever reason, I don’t understand, but I know she had to come home to get the other kids. She left me in the care of someone. I believe they didn’t want to give me back. She had a hard time getting me back. Finally when she did get me back I was only able to be home for about a year before I got sent to the Residential School. I think it had a lot to do with the Indian Agent at the time. Big families, you know, single parents, struggling. They didn’t help much with that.

Je crois que ma mère pensait qu'elle faisait la meilleure chose pour nous à l'époque.

Q. Parliez-vous votre propre langue traditionnelle à la maison ?

R. Pas au début. Mais l'année où j'étais là-bas, j'ai beaucoup ramassé. J'étais un apprenant rapide.

Q. Quand vous étiez à l'école ?

R. Pas à l'école, à la maison, dans la réserve.

I remember them saying, too, when we first got there, “anyone caught speaking that Mi’kmaq language, that savage pagan language – that’s what it was, that pagan language – will be punished.

They had quite a few rules. I don’t really remember them all now. But I probably would if I thought about it. I would remember more.

So we’re in school during the day and then you get lunch. It was short. Recesses. No, I don’t think we really had recesses. School went from 9 to 3. We had lunch and then we had recreation after, from 3 o’clock to 5 o’clock. Five o’clock was supper time. It was pretty regimental. So a typical day starts by getting up at 6 or 6:30 and you do your —

Quiconque va être puni le sera alors. Tout le monde fait ton lit. Descendre. Laver. Brossez-vous les dents, lavez-vous le visage et les mains, peignez vos cheveux, bla, bla, bla. Faire la queue. Attendez que la cloche sonne, que la religieuse vous amène à la cafétéria et que chacun prenne sa place. Chacun s'est vu attribuer une place. Même chose à l'heure du déjeuner.

La salle de classe. Descendre. Laver. Faire la queue.

Q. Beaucoup de files d'attente?

A. Beaucoup de files d'attente, oui, beaucoup de files d'attente.

Q. Alors, qu'est-ce qu'un déjeuner typique ?

R. Ils avaient beaucoup de soupe et de ragoûts. Ils avaient une ferme en contrebas et cultivaient leurs propres légumes.

Q. Est-ce que les enfants travailleraient à la ferme ?

R. Pas habituellement les petits. Je connais un de mes frères aînés, il y travaillait à la ferme. Je pense que 2 de mes frères y travaillaient. Et au fur et à mesure que mes autres frères grandissaient, ils y travaillaient jusqu'à leur départ, jusqu'à ce qu'ils soient en âge de partir seuls.

Q. Avez-vous déjà vu vos frères lorsque vous étiez à l'école ?

A. Sometimes. We would be outside. We were all separated, you know, boys’ side and girls’ side. Sometimes I would get to see my brother. We would sneak around the back. You had to sneak around an awful lot and not get caught. Some of the Nuns were quite vigilant. They had their places where they could spy, but we knew all their places where they spied and we could look up in certain areas sometimes and know that they were there. We would sneak around. There were ways.

Q. Qu'en est-il des soirées, après le dîner, comment passeriez-vous vos soirées ?

A. It wasn’t just me. Evenings I can’t recall myself too many evenings, how I spent my evenings. How I spent my evenings was being punished for anything. It was morning, afternoon and evenings. I was isolated an awful lot there, I feel, anyway, that I was isolated an awful lot because I was a constant bed wetter. I got punished for losing a sock or a handkerchief, or having dirty underwear.

Q. Donc, ce genre de punition s'appliquait quotidiennement ?

A. For me, yeah. So I would be made to stand in the corner for a couple of hours, until supper time. I didn’t spend too much time outside. But every time we were outside it didn’t matter. I think everyone was thrown out every day, rain or shine, snow, blizzard, it didn’t matter. I guess they thought fresh air was good for you. It didn’t matter if it was rainy, or what kind of weather it was. The fresh air was good for you.

But you didn’t see them out there! You didn’t really see them out there all the time.

Q. Y a-t-il des expériences qui vous ont marqué et que vous aimeriez partager avec nous ?

A. There’s a lot, really, that kind of stand out. Seeing others punished —

The beatings were pretty bad. They were pretty bad. These girls would be screaming, not only me, but I would see some of the younger ones and they would have this big ruler. You don’t even have anything here that compares to what —

I can’t see anything here that compares to what they had. Everything was big. To me it was big because I was so small. I was a scrawny little thing. To see little ones jumping around, trying to avoid it. You can’t avoid it, you know. It’s like doing a little dance. They whacked hard. That particular one, Sister Gilberte (sp?) was really good at it. She never missed, barely.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous d'avoir eu des bleus ?

A. Always bruises. Always sore butt. Sore knuckles. Sore head. My ears would be sore from her pulling them. I’ve seen her lifting girls right off the floor holding them by their ears. I’ve seen her lifting them up with both hands around their necks. She used her fists an awful lot, too. She used her fists. If she had anything in her hand —

Cela la blesserait si elle utilisait ses poings, vous savez, alors elle essayait généralement d'avoir quelque chose dans sa main tout le temps. Elle était la plus méchante là-bas. Il y avait d'autres moyens, mais c'est elle qui me hante encore aujourd'hui.

Q. Quelle a été la pire chose qu'elle vous ait jamais faite ?

A. She tried to drown me, I guess. I remember one of my bed wetting sessions, she dragged me downstairs by my ear. She was sick of it. She was going to do something about it. She dragged me all the way downstairs by my ear. She turned the hot water on in that tub and stripped me and put me in there. And of course all the others were following down because it was the morning routine. You have to go down anyway, and brush your teeth, wash your face and hands, comb your hair and get ready for breakfast. So the others weren’t too far behind.

She was quick. By the time they got down I was already in the tub. I was thrashing around and I was turning all red. She put me under. I remember choking thinking I’m going to die and nobody is going to help me. Nobody helped me before. Right? And I went down again. She pulled me up in time. But it was hot and I was already all red. I was red all over and she was hollering and screaming “I’m sick and tired of you wetting the bed.” “Why do you keep wetting the bed?” “There’s nothing wrong with you.” “God is going to punish you.” “You’re nothing but a little savage.” “That’s why you are wetting the bed because you’re just one of those little savages, blah, blah, blah.”

She’s going on and on and on. Of course I was screaming and hollering and crying, struggling because I couldn’t really defend myself. I was in a helpless situation and in a helpless position. I remember going down again. I don’t know if it was for the third time, but I didn’t think I was coming up.

Q. Vraiment?

A. I didn’t think I was coming up. I believe one of the other Nuns grabbed her. I know I got pulled out. I don’t know if it was one of the other Nuns, or a Nun and a couple of the older girls there that rescued me from her. But I believe I would have died if there had not been that intervention that time.

J'ai vu cela arriver à quelques autres filles.

It’s kind of hard to understand how they could be so cruel like that. There were a select few that really got it pretty bad. I know I was one of them. But there were a few others that got more or less the same treatment.

La même chose m'est arrivée quand j'étais plus âgée, mais elle a utilisé de l'eau froide. J'ai lutté cette fois. J'étais beaucoup plus grand et beaucoup plus vieux.

Q. A-t-elle encore essayé de vous maintenir sous l'eau ?

A. Yeah. But I was bigger then. I was bigger then so she couldn’t do what she did to me the first time. I had to be saved the first time. The second time I was a little older and I saved myself. I think maybe the Creator saved me, too. I think that had a lot to do with that.

Q. Elle le ferait aussi à d'autres enfants ?

A. Yeah, on occasion, when her temper flared, when she had reached her limit of what she could tolerate, or when she was just in the mood apparently. I don’t know.

Q. Que diriez-vous de rentrer à la maison en été. Comment c'était ? Votre famille vous a-t-elle manqué et était-ce difficile de retourner à l'école chaque année ?

A. It was hard to go back home even. Some years I didn’t get to go because, well, I think my mother wasn’t around. I think my mother had gone somewhere. I think the first year I went home. The following year I might have gone home, but the year after that I think I had to stay and every year after that, either I stayed or my aunt took me in. I stayed with my cousins, me and some of my younger sisters, and some of my older sisters would stay with my aunt.

They call her “Doctor Granny” now, but I think the most that were in the house, in her small house, were like twenty-seven of us one year, because it was my sisters and brothers and her kids.

Q. Comment était-ce de rester à l'école pour l'été?

A. Même-vieux-même-vieux. C'était pareil. C'était une corvée. C'était pareil. C'était juste la même chose. J'ai encore les punitions.

Q. Êtes-vous allé à l'école aussi? Y avait-il des cours ?

A. No. Some of my sisters and brothers would get to go here and there. I don’t know if they went to the —

Some family would take them in, you know, but they would come back saying they hated it because they were slaves. They were treated just as bad where they were as they would have been if they had stayed. I can’t say anything —

I can’t remember any good times when I stayed, really. I can’t really remember any good times because I was still a bed wetter and I was still getting punished. I had more chores to do because there were less people there.

Q. Donc, vous avez passé la majeure partie de la journée à faire des tâches ménagères ?

A. I spent a lot of the days doing chores. I don’t remember too much having fun kind of stuff. I had a few best friends there, but I can’t remember too many of the good things we did.

I remember I was able to go swinging a few times, on the swings. We used to push each other on the swings, and then when they get high we’d duck under, take a chance and duck under. I remember one time I didn’t duck in time and I got hit and thrown in the air and flew against a tree, a little fir tree that was there broke my fall. Otherwise I probably would have landed further back. I’ve still got a scar. I ended up with 6 stitches.

I remember the Nun coming out. I’m there bleeding and everything, and she came over. The girls were trying to take me inside. “Oh, she’s going to punish me, she’s going to punish me, she’s always punishing me.” I didn’t want her to see me like that. But there was blood everywhere. I couldn’t hide it. I got it all over my shirt. “Oh, she’s going to beat me.” I’m there crying, you know.

She came out. She looked at me and gave me a few knocks on the head and grabbed me by the ear. “Look at what you’re doing.” “Gawd”, she said, “you’re nothing but a bunch of savages, all of you.” Now I gotta take her to the doctor. So I had to go get stitches. She was very pissed off about it, you know, no sympathy.

Q. Aucun câlin jamais?

A. Jamais de câlins, non, jamais de câlins. Jamais de réconfort de sa part, en particulier, en tout cas.

Je pense que la seule nonne qui m'a jamais réconforté, pris dans ses bras et m'a fait me sentir bien, et je l'aimais, et beaucoup d'étudiants l'aimaient, était sœur Agnès Marie. Elle était notre professeur de quatrième et cinquième année. Elle avait la quatrième et la cinquième année d'un an. Nous l'aimions tous beaucoup. Nous l'aimions vraiment vraiment. Elle était comme une sainte.

Ils se sont débarrassés d'elle. Ils l'ont laissée partir. Ils l'ont laissée partir.

Q. Savez-vous pourquoi ?

A. Because she tried to stick up for us, I believe. She tried to stick up for us. They wouldn’t have none of it.

Q. Je veux parler un peu de votre guérison, mais avant de continuer, y a-t-il des dernières choses que vous aimeriez dire sur vos expériences ?

A. Well, there’s so much more to say for that matter.

It was a bad thing, a wrong thing. How could people —

I talked to a friend of mine last night. We were outside talking and he asked me how I got through all of this. How did you start healing? I says, “It took a long time.” All those years I put these people up on a pedestal. They were next to God. No matter what they said or did, it was like God spoke. They were up there with God. Nobody could believe that they could ever do any wrong, I felt.

J'avais l'habitude de planer, tu sais. J'avais l'habitude de planer tout le temps. C'était pendant l'un de ces effets, j'appelle ça une expérience spirituelle quand je plane, il n'y avait rien de religieux là-dedans, rien de religieux à planer. C'était juste pouvoir être ailleurs.

Well, one of these times I was somewhere else and it’s almost like a voice spoke to me and says, “They’re only human, they’re only human”.

— Speaker overcome with emotion

Je pense que c'est à ce moment-là que j'ai commencé à guérir. C'étaient des êtres humains et je pouvais les abattre et me mettre à leur place.

Q. Êtes-vous actuellement impliqué dans des programmes de guérison?

R. Oui, le mien, en gros. J'assiste à des rassemblements et des choses comme ça.

Q. Et si vous faisiez votre art ?

R. Oh, je le fais souvent aussi. J'ai toujours voulu être un sauvage, un païen et un Indien, et je l'étais. Une partie de cela était le perlage, les paniers, la langue, vous savez. Je n'ai jamais vraiment appris à parler la langue, mais je sais comment faire le perlage, le bricolage et tout ça. J'ai adoré la langue, la musique.

Q. Trouvez-vous la guérison dans cela, en faisant le perlage?

A. Oh yeah. It takes me back to the good things. It does. It’s a part of the spirit that they can never take away. Someone even said somewhere that I read, as long as there’s one bead, one rock, one stone, one feather in this world, there will always be an Indian. They can never take that away.

Q. Merci d'être venu aujourd'hui et d'avoir partagé avec nous. Vous avez fait un très bon travail. Merci.

Ah oui.

Q. We’re done. Are you okay?

A. Yeah. But like I said, there’s a lot more to say.

Q. Our hour is up now. But if there is more you want to say, we have the audio as well, and they are not booked up. We have someone else coming right away for a video, but you’re welcome to do an audio.

R. Je peux faire les deux. Je pense que oui.

Q. Yes, do the audio. Lots of people come here and then they realize they should have said this or talked about that, so that’s another opportunity for you if you want to sign up for the audio.

— End of Interview.

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac