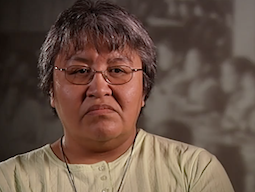

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

L'INTERVIEWEUR: D'accord. Si nous pouvons commencer par nous dire votre nom et l’épeler pour nous, pour la caméra, s’il vous plaît.

GEORGE FRANCIS: My name is George Francis. I’m from Eskasoni.

Q. Eskasoni?

R. J'ai été emmené en 1951.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous alors?

A. Environ onze ans, environ dix ans. Je suis né en 1940.

Q. Vous avez été emmené. Pouvez-vous parler de ce dont vous vous souvenez du premier jour où vous avez été emmené?

R. J'ai été emmené. Nous sommes descendus. Nous avons voyagé en train pendant environ dix heures pour nous rendre au pensionnat de Shubenacadie. Nous étions tous heureux d'aller quelque part. Mais quand ils nous ont dit que vous deviez vous déshabiller et mettre leurs vêtements, hein, ce qu'ils avaient pour nous. Ils avaient pour nous des chemises de la GRC, des pantalons de la GRC et des bottes de la GRC. Les bottes étaient bien sur la semelle lorsque je les ai mises la première année. Mais à la fin de l'année, les semelles sont tombées sur moi.

Q. Vous ont-ils donné de nouvelles bottes?

R. Ils m'ont donné une autre paire environ 2 mois plus tard.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous d'autre chose de ce premier jour?

A. The first day. We went to school wearing all these “Johnny” clothes. People, my children, call them “Johnny” clothes now. I wouldn’t buy them “Johnny” clothes; no way. I bought them the best clothes they ever had.

But in Residential School you don’t get anything best.

Q. Pouvez-vous nous parler d'une journée type, à quelle heure vous vous réveilliez le matin?

A. We woke up in the morning at 5 o’clock. We heard the sound of a stick on top of the drawer. The drawer was about —

Everybody’s boxes were all lined up, and when the Sister went like that (indicating) on top of the drawer with a stick, it means we had to get up. We took a shower. There were twenty-five of us in the showers. There were twenty-five stalls. We were timed. They tell me, “wash your neck, clean your neck with a scrubbing brush.” “Clean your hands with a scrubbing brush.” But they never told me “clean your face with the scrubbing brush”. I wouldn’t have done it anyway. They gave me a face cloth to wipe my face and I washed my hair. There were large combs to comb my hair.

About forty-five minutes later we were ready to go to school for 8 o’clock, the first day of school.

I was a little humiliated by these clothes I was wearing. The Sister over there slapped me and everybody laughed. On another occasion everybody was suspended, everybody has to stay during dinner, the dinner hour, and later that day had to stay until 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

Q. Et le petit-déjeuner. Qu'aviez vous?

A. Petit déjeuner, nous avons eu du porridge tous les matins, trois cent soixante-cinq jours, nous avons eu du porridge. Pas d'oeufs. Mais nous avions du pain. Nous aurions 2 morceaux de pain. Si quelqu'un vous prend votre pain en passant, vous n'avez plus de pain, alors j'ai gardé ce pain.

I can’t dare to fight because the other boys told me that if you fight for bread you won’t get nothing for a week, no bread for a week.

Q. Êtes-vous allé à la chapelle le matin, ou quelque chose de ce genre?

A. Yeah. We went to chapel every morning. We said the rosary then down we go to school. About 5 o’clock or 6 o’clock, after supper, we go to the chapel again and say the rosary in English.

Q. Parliez-vous votre langue avant d'aller au pensionnat?

A. Yes, I did. But I was prohibited from using my language. They wanted to understand what I was saying. I hardly spoke English. I had broken English. While I was there, every now and then, they would bang me on the head and bang my hands and the Sister told me, “okay, put your hand out.” I put my hand out. She hit me with a stick.

And then a couple of months later I was so frustrated I didn’t even see my sister.

Q. You didn’t see your sister from your first day you went there. You couldn’t see her?

A. I couldn’t see her.

And my uncle visited us, Uncle Roger Gould (sp?) from Eskasoni. He took some pictures. I don’t know if he took some pictures of us. He was told to get outta here. He was told it was an invasion of privacy.

Q. Savez-vous pourquoi il est venu prendre des photos?

A. He knew I was there. You know, he’s my greatest uncle. I love my uncles. He said, “When I come again in the spring time I’ll bring your mom and dad.” He was talking to me about it. He was prohibited. I suffered the consequences for that.

Q. Que s'est-il passé?

A. I stayed in the washroom with soap in my mouth because we were talking Mi’kmaw. One of the boys from Memberton said, “I wouldn’t do that.” “Throw the dam soap away.” So I became a radical over there, untrainable. I loved what they were teaching. I loved math. And history, I couldn’t get it, you know, because they were treating us different from what it says in the history books. “Nuns are kind”, and all that. Nuns were not kind in the Residential School.

Q. Pouvez-vous nous raconter certaines de vos expériences au pensionnat?

A. I ran away in the spring time. I ran away. When I ran away when I reached —

Near Stewiacke, about a mile or a half a mile from Stewiacke, I didn’t know what distance it was. I was treated not as the other boys were, eh. I was in the soap room for 4 days, no lights. But I was given food twice a day, in the morning and in the evening.

Q. What’s the soap room?

R. La salle de savon est l'endroit où se trouvait autrefois tout le savon, hein. Dans quelques années, ce serait parti.

Q. Est-ce là où vous avez été mis lorsque vous vous êtes enfui, pour votre punition?

A. Ouais. C'était ma punition.

Q. Pourquoi vous êtes-vous enfui?

A. Because I was tortured by the boys, not by my own guys, my own friends, but they know how to intimidate a person. There was a guy named Nelson Paul (sp?) who used to beat me up when I got out of school and we were on the playground, playing rugby. He used to punch me in the mouth and punch me in the face. My friend told me, “George, don’t take that, fight back.” I fought back and I beat him. But I didn’t beat him to death. I maybe beat him until he said, “Okay, I give up.”

Q. Que feraient les religieuses si elles vous voyaient combattre?

R. Ils nous auraient battus avec un bâton. Le bâton mesurait environ un demi-pouce carré et environ 3 pieds de long. Tout le monde en avait peur, même les petits enfants.

Being in Residential School was no fun. I thought it was going to be fun. At Christmas time they didn’t give us anything. What my mom sent to us was not even shown. My mom told me that she sent a lot of candies over.

I started rebelling the second year. The second year came after the first year was over and we went home. The second year we came in, we went back to Shubenacadie Residential School and we were playing rugby and everybody was tackling me, just like they were tackling a guy over in the bar. I fought back. In the second year I was sent to see the Priest. He said, “You’re fooling around in school, in class.” I said, “I never fool around in class, I try to learn.” He said, “You’re not learning, you’re fooling around.” “That’s what the Sister said.” And me and Paul Isaac (sp?) were punished for all that. Paul Isaac (sp?) was from Bearhead (ph.) Chapel Island (ph.) And my other friend, Noah, said, “George, just be cool about it, try to take everything in stride.”

If you get out of hand, I don’t know what to tell you.

Q. Comment avez-vous été puni?

A. I was punished with the stick. I hated that dam stick. This one Nun she gave me ten straps on my buttocks. I wouldn’t take it any more. She only gave me 9 of them. I took that stick from her and broke it. I was sent to the Infirmary. The Infirmary had two doors; one nice door for the Infirmary and the other one is inside, it’s like a cell door. You’re not going to get out. There were bars on the window and bars on the door inside, locked from the inside, eh. And the Sister had the key.

And I had to pay all these things which I didn’t do.

My work was alright. And my association with the other boys was alright, except one, Nelson Paul (sp?) I always got into fights with him. That stopped the second year because I beat him up. I didn’t go on trying to kill him or anything, so I just let it go.

I tried to finish my second year. We were playing rugby, eh. I was talking Chibooga (ph.) I was talking to Eugene Paul (sp?). He was from Eskasoni. I told him, “Chibooga (ph.)”. I’ll go. I didn’t know the Sister was right in the doorway and she heard me. She said, “George Francis, come in.” I got strapped again. I didn’t say that inside. It was prohibited inside. But I didn’t know it was even prohibited outside.

Q. Aviez-vous des frères et sœurs à l'école?

R. J'avais 1 sœur; Shirley.

Q. Avez-vous déjà vu Shirley?

R. Non.

Q. Elle vous a manqué?

R. Elle m'a manqué. Après cela, quelques années plus tard, elle est allée à Boston. Elle s'est mariée avec Gilbert Julian (ph.) Et ils avaient une maison à Eskasoni. Je leur ai rendu visite tous les jours.

Q. What’s your worst memory of Residential School? Maybe you can tell us your worst memory and then maybe if you have a best memory.

A. Worst memory is the Priest fighting me, eh. The Sister, when I threw that stick in half, they dragged me to the Priest and he told me, “George, tonight we’re going to box.” I was waiting for it until about 8 o’clock, after he beat up Frenchy, Frenchy Bernard (sp?) He was a small guy. He beat him up, you know. His face was all red in blood. And Noah told me, “Okay, he was putting on my gloves, eh, he wasn’t waiting, the Priest wasn’t waiting for if I had gloves on or anything. And there were 2 fellas tightening my hands and Noah told me, “Okay George, pretend that you fall, just pretend, don’t fall right to the floor, but pretend that you tripped and smack him right in the balls.” That’s what he told me. And I did that. The Priest fell right on the bench, the hardwood bench. It was about that wide and about that high (indicating). He had blood all over him. There was blood all over the floor, and after about fifteen minutes I had to wipe the blood off.

That was near the —

That was around I would say about March, potato season. So he never bothered me again. But he says, “I’m keeping an eye on you.” He never bothered me.

J'étais alors un garçon de ferme.

Q. Avez-vous appris l'agriculture au pensionnat?

R. Oui.

Q. Pouvez-vous en parler un peu?

A. We went at 5 o’clock in the morning to milk the cows and put those suction things on them. There were about two hundred and fifty cows. The milk went right into the tanks outside. I worked there for about 3 months.

Then I got into a fight. Bill Watts (sp?) came over and threw me on the ground. He threw me about – I wasn’t big then – it must have been about from here to the corner over there (indicating), right under the hay wagon. There were bundles of hay. I watched him walk back across the road and he brought a hay rake. You know them hay rakes that are made of wood? They are about 4 ½ feet wide. He hit me on the top of my head, right over here (indicating), on the side. All the boys were watching: Eugene Paul and Noah Christmas and the other boys. And Eugene said, “George, are you all right?” I couldn’t see. I was blacked out for a couple of seconds. I knew something was wrong because I had never had that before.

Quelques années plus tard, environ 2 ans plus tard, j'ai commencé à avoir des crises d'épilepsie. C'était la deuxième année plus tard après être allée à l'école, je suis sortie du pensionnat le 29 juin et c'était ma deuxième année, c'était la dernière année. Je sortirais et j'allais bien. J'étais content de sortir.

Q. En quelle année êtes-vous sorti?

A. 1952. I stayed from 1951 to 1952. But each summer I go home, eh. They gave us no clothes. I don’t know whose clothes it was.

Q. Vous aviez travaillé à la ferme laitière. Y avait-il une autre agriculture à l'école?

A. There was a —

You know, when you slice a potato you look for one eye over here and the other eye over there, you split it in half. That’s what we were doing. I know that. It’s something I seen my father do.

Q. Il y avait donc également une ferme de pommes de terre?

A. Ouais. Et nous avons eu nos carottes et nos navets. Ils avaient tout ce dont nous avons besoin pour manger.

Q. Alors, comment était-ce de rentrer à la maison après cette année au pensionnat?

A. My father said, “George —“

I told my father about my experiences in Residential School. He said, “I’m going to Brad McCain (ph.)” We’re going there tomorrow. That was going to be Monday. We went there on Monday morning. We got to Brad McCain (ph.) and my father was mad, mad as hell. I never had scars before, on the head, anyway.

About 1953 I started getting epileptic seizures. That was before. 1952. In the summer me and my sister were going to go to a baseball game is Eskasoni. She always told me, “George, hurry up.” That’s when I told her, “you go.” My feet were moving, not by me, I wasn’t moving them, but they were moving. So I said, “There’s something wrong.” I was scared. Geez, I was frightened. When they took me to the doctor the doctor prescribed pills, Dilantin (ph.). He gave me 3 Dilantin (ph.) “Take these”, he said. That was in Sidney. They called it the Marine Hospital.

I fell at the Bingo Hall, right on the steps. So the cops took me in and told me that I was drunk. So I called up Louie Adegny (ph.) who was the Chief and the Hospital Director (ph.) at the same time. He said, “you’re drunk?” “You weren’t drinking last night.” “You weren’t drinking this morning.” So he came over and got me out. He had a lawyer with him. Then he told the cops that if they ever touched me again there would be consequences. “He’s got epilepsy.” Everybody falls with epilepsy. I’ve been suffering with epilepsy for numbers of years.

Q. Et l'épilepsie est le résultat d'un coup?

— Transcriber’s Note. Recording abruptly ends at this point but continues on the next track.

R. Le seul bon souvenir que j'ai, c'est quand ils l'ont déchiré.

Q. Quand est-ce arrivé?

R. Il y a quelques années. Ils l'ont démoli.

Q. Vous y êtes-vous rendu le jour où ils l'ont démoli?

A. No. I didn’t want to.

Q. Donc, vous y êtes resté 1 an?

A. Deux ans.

Q. Deux ans. 1951 et 1952.

A. Ouais.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous en 1952?

R. J'avais douze ans.

Q. And why didn’t you go back?

A. My father talked to the Indian Agent, Brad McCain. He had a talk with him and he was mad. When I got that first epileptic fit, holy gawd, they took me to the hospital and took me for check-ups everywhere, even to Halifax over here. So I’ve been having epilepsy for a number of years, just because of a Priest.

I’ll never forget it. But maybe I will, after talking about it like this now, maybe I’ll forget about it.

Q. Lorsque nous parlons de guérison, y a-t-il d'autres expériences qui vous sont arrivées au pensionnat et que vous souhaitez partager avec nous?

R. Non.

Q. D'accord.

R. Il ne m'est jamais arrivé de mal, mais j'ai entendu dire que beaucoup d'enfants avaient des problèmes, hein, des petits enfants, des grands garçons après eux des enfants. Et ils se sont fait prendre, environ quatorze d'entre eux.

Q. Et votre guérison. Allez-vous à des événements de guérison ou quoi que ce soit. Que faire?

A. I go to every healing event there is. I even talked to the Priest one time in Eskasoni. His name was Father Holly (ph.). I used to talk to a lot of them. But there was another Priest who was a little aggressive. I told him, “you know, he told me that I should be working with him, eh, helping him.” I told him that I was working in the Residential School and nobody gave a dam about me. So why should I help you? You are a different Priest, but you know. But he’s still a Priest. He’s just bossing people around. I’m not your boss.

Q. Que diriez-vous à ce prêtre, celui qui vous a frappé à la tête, si vous le voyiez aujourd'hui?

A. Today, I’d probably choke him to death, see how it feels, as he choked me. He hit me with the stick and the strap. That only happened about —

Le premier mois, je suis allé à l'école, et cela s'est reproduit la deuxième année lorsque je suis retourné à l'école.

At the end of the year when she asked me questions about education, I knew them all. Still they said that I was cheating. I had nothing to write on. Because I was studying. I didn’t want to get into any more trouble.

Q. Et après les pensionnats indiens. Qu'est-ce que tu as fait?

R. Après le pensionnat, j'ai travaillé comme coupeur de pâte. Je coupais de la pulpe. J'ai travaillé pour Douglas Denny (sp?) À Eskasoni. Nous coupions de la pâte. J'avais environ dix-neuf ans.

Q. Aviez-vous douze ans lorsque vous avez quitté le pensionnat?

R. Oui.

Q. Qu'avez-vous fait de l'âge de douze à dix-neuf ans?

R. Je suis allé à l'école Eskasoni. Ils m'ont ramené.

Q. Était-ce une école de jour?

A. Le externat indien.

Q. Avez-vous aimé cela plus que les pensionnats indiens?

A. Yeah. It was better. We had more freedom. At recess time you can have conversations in Mi’kmaw with people.

Q. Avez-vous des enfants. Es-tu marié maintenant?

A. I was married in 1976. We had two boys and two girls. In 1972 my wife went away. She says she was going to get time off for one of the girls, Carla. And she was going over to her grandmother’s place. It’s only about a hundred and fifty feet from us. She never came back. She never came back. I never looked for her. But I heard that she was in Toronto. But still I never looked for her.

Q. Et vos filles. Les voyez-vous encore?

R. Oui, je les vois toujours. J'ai de bonnes relations avec nos filles.

Q. Pouvez-vous leur parler de vos expériences au pensionnat?

R. Oui, je leur parle. Ils savent tout. Tout ce qu'il y avait à savoir. Ma mémoire est un peu fausse, mais quand j'étais jeune, ma mémoire était exacte.

Q. Vos filles ont-elles dû aller au pensionnat?

A. No way. I wouldn’t let them. I would die first before letting them. I would kill for them. I would have killed for them.

Imaginez-moi avoir quatorze armes dans mon salon. J'aime chasser; lapin, cerf, mais pas orignal.

Q. Avant de terminer, y a-t-il une dernière chose que vous aimeriez dire?

A. I wish they never build another Residential School ever. People like me who suffered —

Another thing I say to my children, bring that to me, they’ll do it. They love me that much.

One rebelled against her mother. She lived up here, a couple of years ago, ten years ago. She beat up her mother. She was drunk and she beat her up so dam bad, her face was swollen and she had a broken jaw and black eyes. I didn’t believe it. But I told myself that I had to see to believe it. So I went to where my wife was. She was laying on the floor. Not on the floor, she was laying on the bed. I told her to look at me. She looks at me. “Who did this to you?” Myra (ph.) “Okay”, I told her. Myra is not going to see you any more. I heard about this, this morning about 6 o’clock. I heard about it. The Mounties came in and said that your daughter beat up her mother.

I didn’t give a dam. That’s what they thought. But I did give a dam. I told Myra “never touch your mom”. You got only one mother in this world and one father, remember that. Don’t ever try that trick again. Try to feel sorry for yourself.

She said, “Dad, I was sorry because of you.” “I was mad.” She was drunk.

Q. Avez-vous des petits-enfants?

A. Grandchldren? I’ve got one in Eskasoni. She’s probably in my house right now; Patty (ph.) And Funk’s baby, Thomas, Brandon. And there’s a little girl. I just forgot her name!

Q. Est-ce que cela vous rend heureux de penser qu'ils n'ont jamais à aller au pensionnat?

A. Yeah. I’m happy.

Q. Merci beaucoup d'être venus aujourd'hui. Nous apprécions vraiment cela.

A. Yeah. Residential School really deteriorated my mind. When I get outta here and go home, I’ll be in peace again, and think about what I missed in this conversation.

What I missed I’ll write it down and send it to you. Or I’ll give it to Laurie and she can bring it over to you.

Q. That would be good. The other thing you can do is if there are other things you remember, there are openings in the audio interviews. You can go and have another audio interview after as well, if there are other things you want to say after. But if you write them down, that would be great. You can send them and we’ll get them.

A. Les écrire est une expression parfaite, les écrire.

Q. Oui.

A. So I’ll know what I’m saying and what I’m going to say in a couple of seconds, I’ll know, because I’m going to write them down.

Q. D'accord.

A. It’s better to write them down than say it again. Sometimes, like before, a lot of information came into my head and some things I didn’t want to say, some things I forgot to say, and you know —

Q. Y a-t-il actuellement des choses dont vous vous souvenez?

A. I was sorry I never saw my parents visit me, or my uncle Rod who came to visit me. He came from Eskasoni to Residential School just to be kicked out. He told me that Priest over there, what’s his name, I told him I don’t hurt a Priest now, but he got tangled up, mixed up somewhere.

I’ll get it. Don’t worry.

Q. That wasn’t important. Well, thank you for coming today.

A. It’s not important anyway.

Q. Non. Et vous avez fait un excellent travail. Vous avez partagé beaucoup de choses avec nous.

A. Son nom était le père Mackie (sp?)

Q. D'accord.

A. Father Mackie. That was the guy that wanted to box me. I had a couple of coaches, two coaches; Paul Isaac from Chapel Island, and Noel Christmas. Noel Christmas and Paul Isaac told me, “Take him in the balls.” So I did, and I did it hard. I did just what they told me. That was the end of my experience in the Residential School.

Q. That’s good.

A. I told my father about it and he freaked out, eh. “You hit a Priest!” You’ll go to hell for that. And I told him, “Well, if we did go we’ll probably be together in hell!” (Laughter) He wasn’t laughing. Today’s Priests wouldn’t do it. Fight children. It was illegal in the nineteen fifties. Because I worked in the jail cell (ph.) in Eskasoni. And when the Commissioner came down I asked him about it. Was it illegal in 1950 to fight under-age kids? He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Why in the hell didn’t you visit those Residential School in Shubenacadie on a monthly basis?” They were beaten. They were beaten by sticks. We were treated more like animals instead of people. I wish he could hear me today.

He’s probably waiting for me.

Q. Merci beaucoup.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac