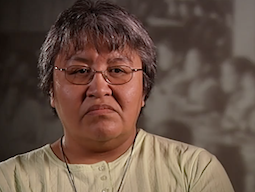

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

THE INTERVIEWER: Grant, I’ll get you to spell your first and your last name for me.

GRANT SEVERIGHT: Grant Severight; Subvention

Severight.

Q. D'accord. Et à quelle école êtes-vous allé?

A. St. Philip’s Indian Residential School.

Q. Où est-ce?

A. Par Kamsack, Saskatchewan. En fait, cela devrait concerner la Première nation de Keeseekoose.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous la première fois?

R. J'avais 5 ans.

Q. Vous souvenez-vous comment c'était votre premier jour?

R. Oh oui, je m'en souviens.

Q. Pouvez-vous décrire cela?

R. C'était un jour comme aujourd'hui. C'était l'automne. J'étais excité. J'avais hâte d'y aller. Ils ont roulé dans un gros vieux camion vert International, un camion à bestiaux. Je me souviens que c'était vert. Je me souviens que mon grand-père m'aidait à monter dans le camion, sur la caisse, pour m'aider à monter. Je me souviens que je me tenais debout et que nous conduisions pendant que nous prenions d'autres élèves. C'était vraiment excitant.

Je me souviens d'être arrivé à l'école. Je pense que ce qui ressort vraiment dans mon esprit, c'est l'odeur du désinfectant qu'ils ont utilisé à l'école. C'était vraiment dur. Chaque fois que je sens cette odeur particulière, j'ai toujours ce flash-back d'avoir été dans cette école. C'était un désinfectant spécial. Je le sens encore de temps en temps partout où je vais.

I remember getting into a fight with another little boy who ended up being my boyhood friend for the rest of the time I was there. His name was Mike. That’s pretty well it.

Et aller au lit. Je me souviens être allé me coucher. Il faisait encore jour. J'ai trouvé cela un peu inhabituel.

Q. Comment était-ce dans les dortoirs lorsque vous vous êtes couché?

A. I remember the bunk beds and how all the beds were neatly made. I remember being assigned a top bunk. And I remember the guy below me. His name was Dennis. I’ll always remember that because he actually wanted the lower bunk and I wanted the top bunk. That’s how we agreed to that.

There again, smells were probably the most distinct thing about Residential School. I remember they gave us powdered toothpaste. I remember the smell of that and the kind of hand soap they gave us. Basically that’s it.

I don’t remember having lunch or anything the first day. We probably did. I just don’t remember it.

Q. Comment était la nourriture là-bas?

A. St. Philip’s was notorious for giving very poor quality food. Why I’m able to say that was I was transferred to another school after to make a comparison. That’s how come —

If I had not been transferred I probably would not have known any better. But St. Philip’s was known for porridge, the hole-y bread, crusty dry bread, the barley soup we got almost daily, the beans —

What we all liked at St. Philip’s we all got wieners and beans or some kind of a bean concoction every Sunday. That was probably the most delicious thing we had there. Fridays we always had some kind of fish. I don’t know what kind, I don’t remember, but it was always fish every Friday.

Oh yes, at supper time the reason I remember that is we used to get canned fruit for dessert and we used to make bets. Sometimes we would lose our dessert or sometimes we would win. That’s what I remember about that. But the food wasn’t the greatest for the students.

I knew it was good for the staff because I was one of the boys later on in life that, later on, we hauled in the truck supplies for the school. When the supply truck would come in every so often, the boys would haul in the goodies. I remember the cases of bananas and the cookies and all that nice stuff. But I don’t ever recall eating a banana in that place, or cookies.

Q. It wasn’t for you guys?

R. Probablement pas. J'ai trouvé ça étrange.

Plus tard, lorsque je suis devenu enfant de chœur, ma récompense a été d'obtenir une orange. Après avoir servi la messe, j'obtenais une orange. Ceux qui allaient se confesser ce dimanche matin seraient récompensés par une orange. Ou si vous êtes allé à la sainte communion, vous avez reçu une orange. Ils avaient un assez bon système d'incitation pour prier beaucoup.

Q. Avez-vous beaucoup appris au pensionnat en ce qui concerne les universitaires?

A. From what I’ve heard, I really excelled in school. I was one of the —

I remember going to a special conference with the school staff. I was supposed to make a presentation to the other school teachers but I was too nervous. I forgot what I was supposed to do and I failed dismally for them so they were kind of mad at me for that. That wasn’t a good experience. But I remember getting good marks.

I guess I couldn’t tell the difference, but the study periods I didn’t like. They were so long. For an hour every day we went to study. And then we had a little recreation program there which was not too bad.

Je n'ai jamais rien vécu de mal jusqu'à plus tard, quand j'étais plus âgé. Mais je me souviens qu'une grande partie de la violence venait des élèves plus âgés, des garçons qui étaient là.

Q. Et les enseignants?

A. The teachers? When I went there the Nuns were on their way out. I’ve heard other people who have talked about them, and the first year I was there they were already doing away with the farm. But they still had animals.

I remember me and my uncle Milton. Milton was retarded and I remember we used to go ride the pigs. We got caught one Saturday morning riding pigs, so we had to give up our Sunday afternoon movie and had to write five hundred times on the blackboard “I will not ride pigs.” I remember that quite explicitly. It probably wasn’t a good experience for the pigs, either. But they didn’t take kindly to us abusing animals, I guess.

The movies were the big highlight there. They had these old reel-to-reel things and you could hear them clicking. It was a big thing for us to go watch especially the Indian and Cowboy movies. We all ended up cheering for the cowboys anyway! Them terrible Indians were driven off the land. It’s crazy.

Q. Que voudriez-vous que les gens sachent de votre expérience au pensionnat?

A. L'expérience en elle-même a disloqué les enfants du noyau de la chaleur familiale et de l'attention familiale.

Q. C'est ce qui vous est arrivé?

A. Yeah. The nurturing. Even though I was raised by my grandparents, I loved my grandparents. I would have stayed in the bush with them rather than being put in a Residential School. I remember missing them and the dislocation I felt, the disconnection I felt to my family. Eventually that whole dislocation and disconnection kind of built walls in me that took me years to deconstruct again. The feeling of inferiority I felt —

All over the Reserve we were happy there but when we would go outside the perimeter we would see these White farmers who were flourishing and just wealthy. Somehow even as a young man I used to wonder why is that? Why is it we don’t have anything and why did I feel different when I went to town with my grandparents? We weren’t treated with any kind of dignity. We were more or less just tolerated by the merchants in town.

Cela a eu une impression durable sur moi, ce sentiment de ne pas être égal. J'ai probablement repris cela dans toutes mes autres relations plus tard. D'une manière ou d'une autre, cela a tiré dans ma colère d'esprit. J'ai vraiment ressenti un traitement injuste. Mais à ce moment-là, je n'avais vraiment rien à comparer avec cela. Je pensais juste que c'était comme ça pour nous les gens.

I remember eventually by the time I was about twelve years old I was already thinking about leaving the Reserve because I seen there was nothing there. Somehow I was born with a desire to want more. I wanted more. I wanted to experience life to a greater degree. All I seen at that time were things I seen in the movies. But I knew there was another world out there and I couldn’t wait. I even tried running away when I was twelve years old. I didn’t get very far. I got hungry so I come home! That was the extent of my escape from the drudgery of living on an Indian Reservation during the summer holidays.

Finalement, j'ai été transféré dans un autre pensionnat.

Q. Quel âge aviez-vous lorsque vous avez été transféré?

A. I was twelve years old. I burnt down a White farm, me and my retarded uncle went. He was the local bootlegger. I remember my grandfather giving his food voucher for wine. I remember I says, “you know because of him we go hungry all the time.” I never forgot that. One day me and my uncle came upon this farm and I recognized the vehicle and nobody was home so we burnt it down.

I got transferred. The police, the RCMP came and got me. My uncle, they didn’t do anything to him because they felt he wasn’t really the ringleader. He was older but they sent me to another Residential School.

Q. Où?

A. In Marieval. That’s about a hundred miles, about eighty miles south. But that’s where I was able to make the comparison.

Q. Comment était cette école?

A. That school was like walking into paradise. It was unbelievable. I remember the Priest picking me up in that little town there where they had put me on a bus, and I was under the care of the bus driver. The Principal picked me up and took me to school. It was about 9 o’clock at night and I remember him taking me to a place where the staff had lunch. I remember getting cookies and a glass of milk. I mean, it was the real milk that tasted good. The other stuff we had was always powdered stuff. I remember, man, was this ever different. And the meals were different. I remember having corn flakes, boiled eggs, toast, and I remember at dinner time we would get hot dogs and bags of chips and hamburgers, and a full course meal at supper time, just completely different.

Q. Tous les jours?

R. Tous les jours. Et je me souviens que les garçons avaient accès à des guitares. Nous pourrions jouer de petites guitares. Là aussi, ils avaient des vélos que nous devions partager. Mec, j'ai vraiment frappé le grand moment ici. C'était un monde complètement différent.

Q. Quel était le nom de cette école? Pensionnat indien de Marieval?

A. Ouais. Marieval était située sur la Première Nation de Cowessess. C'était aussi une école oblate. Mais c'était différent.

Over the years when I did my studies and when I looked at why things were like that, the St. Philip’s one was really trying to prove that he could run a school on a very small budget, so consequently we weren’t fed that well. But he eventually got transferred and got promoted. Father Sharon (ph.) became the Principal at the Lebret Indian School, which was the elite of a lot of the Indian Residential Schools in the west. By saving money, I’m just speculating about what he did at St. Philip’s, he earned his promotion to Lebret.

Marieval was situated by a lake. It was kind of a resort area. I remember going out to the lake on weekends fishing, going camping, wiener roasts, a completely different thing than St. Philip’s.

Q. Y a-t-il eu un type de violence dont vous avez entendu parler là-bas, comme la violence physique?

R. À Marieval, il y a eu des abus sexuels. J'ai été victime d'abus sexuels, mais c'était de la part de garçons plus âgés, pas du personnel.

Q. Où pensez-vous qu'ils l'ont appris?

A. Well, we don’t know. There were 2 supervisors there who were sexually —

The guy that was —

He didn’t injure me or anything but he used to fondle me and that kind of stuff. But he learned it from a supervisor. He used to tell me. He learnt that off Brother so-and-so. George did pass away after he left school, but he was the guy who used to do that kind of stuff.

We were different. The reason Marieval was different was Sundays they used to dress us up. We wore these little ties. It was a big deal to go to church and they dressed us up. We would go bowling. They had a little bowling alley there, of all things. And then we had bazaars and we could win prizes. St. Philip’s was just —

When I talk to the students who went to St. Philip’s the whole time they were there it’s almost unbelievable what I tell them. Weren’t all schools the same? I said, “No, they weren’t.”

We found out right through history, through different studies that St. Philip’s was deemed to be one of the worst Indian Residential Schools.

Q. St. Philip’s?

R. Oui. Pour le traitement, oui. Il était courant que le prêtre ait des rapports sexuels avec les filles plus âgées. Le prêtre avait une liaison avec la sœur aînée du personnel, ou l'une des femmes, Miss Lalonde qu'ils l'appelaient.

Q. Comment savaient-ils cela?

A. The parents used to tell us. They used to catch them on a Reserve road, or something. You know how Indians are, they talk, you know. But as good little Catholics we never paid attention to that kind of stuff. But throughout time I come to believe it because Father Sharon (ph.) spent a lot of time with that lady. That’s where my sexual abuse happened was in St. Philip’s.

Q. Des garçons plus âgés?

R. Non. Du professeur de musique.

Q. Un homme?

A. It was a man. Yeah. I was the one that broke the case in St. Philip’s, right after Gordon’s, about 2 weeks after Gordon’s broke their case, I got wind of it and I did the same thing with St. Philip’s.

Je suis devenu un défenseur de toutes les affaires des pensionnats parce qu'en 1982, j'écrivais déjà des articles sur ce qui m'est arrivé au pensionnat.

Q. Pouvez-vous décrire cela?

A. I had gone to bible school in my search for significance. I was trying to find my spiritual way because I had been taught that my way was of the devil and you had better not go there. So I became a Christian for a while. But then the professors used to tell us to write about significant things in your life, so I started writing about what happened in Indian Residential School. I remember the one professor saying, “Grant, your writing is strong. We can feel the pain in your writing. We can feel the hurt. It’s so powerful.”

But I didn’t know what they meant by that. So I just kept writing, not realizing already that I was starting to disclose in the safest way I knew without getting judged.

Q. Que vous est-il arrivé alors?

A. I was sexually molested by a school teacher, I mean not a school teacher, but the music teacher. He used to take me into piano practice during study sessions. He would come and get me from the classroom and take me to the room and do funny things. He used to pay me. He used to give me money for it. I didn’t really like it. For awhile I thought I was the only one that he was doing that to, so I kept it kind of to myself. I never told anybody because of the shame and maybe the boys would make fun of me.

But then I started noticing he was taking other boys and one day I kind of followed, just kind of sneaking behind. I was peaking through the curtains to see if that boy was actually having piano practice but he wasn’t. That man was sexually fondling him and kissing him. So I thought, okay, there’s somebody else. That made me feel a little bit better.

Mais j'ai confronté ce type parce que je voulais savoir ce qu'il en pensait. Il l'a nié.

Q. À votre visage?

A. “We don’t do that”, he said.

Q. L'avez-vous confronté en tant qu'homme adulte?

A. No. I confronted him as a boy, the other guy that was being molested. I said, “Does Mr. Gray do these things to you?” He said, “Oh no.” But you could tell how he put his head down. And then shortly after that I started noticing other boys. He took favour to other boys. Actually, during the Christmas holidays he would travel to Florida, and during the Christmas holidays he would take these boys with him. He would take one boy at a time to Florida or to Montreal. I said, “Wow.”

Later on in life I asked this man, I said, “You need to be honest with me, what happened on those trips?” But they wouldn’t talk but I knew by their not talking they were saying things used to happen.

There was a guy just before that, another Priest, his name was Father Lambert, and I remember the boys talking about him, but he didn’t do anything to me. But it was interesting in my travels, though, I found out he was Phil Fontaine’s abuser, Father Lambert, because he did go to Fort Alec after that Priest.

Q. Je me demande s'il est toujours en vie?

A. Father Lambert? No. I talked to Phil about him about 5 years ago. He passed away. But he just laughs, you know. I said, “Phil, you know what he used to do.” As men we found ways to kind of laugh about it. But me and Phil became close because of our shared commonalities with what happened to us as boys.

Q. Avez-vous déjà eu la chance d'affronter le père Lambert?

A. Some guys did. One of the boys that he did molest confronted him in the Residential School in Fort Alec. They went up to pick up a fire engine and he was there. He tried to grab that boy on his bum and he was already a young man, eh, so that young man confronted him. He did a lot of damage to a lot of young boys. He just walked away. But he sodomized kids, that guy, lots of them, lots of young boys. He was probably the worst abuser that I’ve heard of so far. But he passed away about 7 years ago.

It’s funny the different people I have run into in my work, how we were connected and how some of us could talk about having the same abuser, you know, it’s just amazing.

Il y a eu une ère de honte, je pense que beaucoup d'hommes ont traversé, des hommes de mon âge dans la cinquantaine maintenant, la soixantaine. S'ils étaient vraiment honnêtes, vous verriez qu'il y a là beaucoup de culpabilité et beaucoup de honte, et beaucoup de colère, de colère non résolue. Beaucoup d'hommes sont morts sans jamais comprendre ce qui leur était arrivé.

I’m just fortunate that this whole thing came out in my lifetime. At least now I can talk about it and I can go back to the Creator with a clean spirit and a good spirit. Because in my work I have come to find that abusers don’t really personalize anything. They just find victims. It wasn’t because of me it happened. I was a very convenient victim for the abuser and I was able to forgive that.

Q. We’re just going to change tapes.

Ah oui.

— End of Part 1

Q. It makes you wonder how Father Lambert was raised and why he thinks that’s good or normal?

A. I really don’t have an answer for that, but that’s just the way he was. He came to St. Philip’s and went to Fort Alec, and I don’t know where he ended up after that. But he certainly had his victims. Some of the guys I talked to said that he really really did damage to a lot of young men, that particular perpetrator.

Q. Connaissez-vous son prénom?

A. No, I don’t. All I know him as is Father Lambert. He was an Oblate. The principal of both the schools in St. Philip’s were not like that. They were more into the heterosexual stuff, they were. I imagine the girls could tell stories about what they experienced in there. But the homosexuals in St. Philip’s, a guy by the name of Ralph Gray, that probably sexually abused fifty boys.

Q. Quel était son rôle dans l'école?

R. C'était le professeur de musique.

Et puis ils avaient un gars du nom de Rocky (quelque chose). C'était un superviseur. Il n'a pas été reconnu coupable d'agression sexuelle, mais a été reconnu coupable d'agression physique sur les garçons.

Q. Quel genre de choses a-t-il fait?

R. Il les a brûlés avec des cigarettes. Il les a fouettés. Il avait l'habitude de mettre en place des huttes de sudation et de brûler les garçons pendant qu'ils y étaient.

Q. Était-il membre de la Première nation?

A. I think he was part First Nation. He was from Alberta someplace. But he was more —

Il a été socialisé White. Il avait des valeurs blanches, mais je pense qu'il cachait sa nationalité à ce moment-là. Il est sorti de l'armée de l'air. C'était un champion de boxe dans l'armée de l'air et très physique. Il a joué dur.

I did talk to him when I was a man and he told me that he never intended harm. “That’s just how I played”, he said. Somehow I can understand that. But a lot of the young boys I don’t think really appreciated the harm, all the physical harm.

When the Star case first came out I couldn’t visualize how one guy could single handedly abuse ninety kids. I said, “That’s not possible.”

Q. Quel était son nom?

A. Mr. Star. I forget his first name. But that’s the Gordon’s case. Here I was thinking, well, what happened to us with Mr. Gray, well Mr. Star could assault ninety boys and Mr. Gray has assaulted fifty young men, but now I can understand how they could do that over the course of time. I think there were over fifty complaints of sexual assault or sexual abuse from Mr. Gray. So it is possible.

Q. So Star was at Gordon’s?

A. Um-hmm.

Q. Était-il enseignant?

A. He was a supervisor, a teacher. Well, he was actually the Principal. And then I’ve heard Plinkett (ph.) from BC, how he assaulted eighty kids. So that’s not unreasonable now. Because I know White society thinks how can one guy do that to ninety kids. But now when I look at it and when I studied it over a course of 5 years, it’s quite possible.

Q. It’s possible.

A. Ouais.

Q. Donc Plinkett était en Colombie-Britannique?

A. Um-hmm.

Q. Savez-vous dans quelle école il était?

A. Kamloops. Il a été condamné et on lui a donné dix ans je pense, là-bas.

Q. Je me demande s'il est toujours en vie?

R. Les gens disent qu'il l'est, oui.

Q. Et Star?

A. Star est toujours en vie.

Q. Où habite-t-il?

R. Je pense qu'il se trouve quelque part sur la côte est.

Q. Connaissez-vous d'autres agresseurs qui sont encore en vie?

A. Not offhand. I haven’t looked at it for quite a while.

Q. Vous travaillez avec des gangs, n'est-ce pas?

A. Ouais.

Q. Pensez-vous que la mentalité des gangs découle des pensionnats?

A. Gang mentality I believe is directly attributable to what happened by the deconstruction —

We don’t have the closeness of family any more. A lot of the grandparents and a lot of the parents who went to Residential School lost that familial sense of belonging. In the course of having grown up like that you always try to emulate the people that raised you. If you were raised in coldness and detachment, you’re going to carry those same ways of raising your own children in that atmosphere.

I know men who really believe that they should break the spirit of their children, to discipline them and to control them. I remember them saying, “break their spirit, break their spirit, don’t give in to them.” That’s exactly what happened to them. The whole consequence of that is men don’t know how to feel, or they don’t know how to show their feelings. There is no nurturing any more. The children are feeling that so as a consequence they are taking it into their own hands by establishing a family system where they feel protected. They feel accepted and they feel it’s a place where they can do something with their lives.

A lot of gangs are selling drugs and it’s a way of life for them and they make good money doing it. There’s lots of sex. There’s a lot of acceptance. It’s a family.

Quand on y regarde en arrière, tout découle non seulement des Autochtones, mais de toutes ces autres personnes marginalisées qui doivent s'organiser et se rassembler pour leur sécurité et pour des sentiments mutuels d'acceptation.

That’s where I kind of learned it. In 1969 when I was in jail, the White population used to run us. They used to boss us. One day I figured out if we organized and fought back that would stop. And we did it. I think in some instances we changed Corrections in Saskatchewan in 1969 because we fought back.

Q. Quand vous étiez en prison?

A. Ouais.

Q. Pourquoi êtes-vous allé en prison?

A. I was in there for stealing cars and just being drunk. When we had a jail riot I got 5 years for trying to hang a prison guard. That’s how come I ended up in the Pen. I was just angry, outright-ly angry, and trying to get a feeling of significance. Our idols, our role models, were guys who came out of jail. They were tough. They survived the system so we looked up to them as real men. We needed to be like them; tough. They defied the system.

Et quand vous regardez ce genre de mentalité, vous pouvez tout remonter au pensionnat. Comment allez-vous rendre quelqu'un fier de quelqu'un que l'on vous a fait croire inférieur? Pourquoi même s'embêter?

We’re in a mess. I keep telling people. I keep trying to tell people that we need to do something with the youth gangs. Phil appointed me to a Corrections Think Tank and I go to Ottawa once in a while. Me and Phil became really good friends, having been on the board of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation together. He lost his election for a while there to Matthew (something), for 3 years. He came on the board with us. I got to know him and I got to tell him of some of the dreams I had of what we need to do, how we need to help our people, our young men.

Q. Comment pensez-vous que nous devons les aider?

A. We need to put value, we need to get our kids feeling good about who they are. We need to teach them that it’s okay to be First Nations, it’s good to be First Nations people. We have a viable culture. We have strong principles. We know what sacredness is, you know, and that our way of seeing the world is probably just as good as anybody else. We need to instill that into our children.

It’s working. It’s coming, but it’s slow. I think we’ve only started our work. The urban centres are the ones that are feeling the whole crunch of it.

The reason I went to Winnipeg was to learn how to work with youth gangs. That’s why I moved there. I sold my house in Saskatoon. I moved up there. I made that whole circle of coming here. I worked in Lethbridge with the Blood Tribe for a while. I worked with their youth.

Q. Y a-t-il autre chose que vous aimeriez ajouter avant de conclure?

A. No. I’m fine. I’m okay. Thank you for letting me share my little story.

Q. Vous sentez-vous bien?

A. I feel better. When I first told my story at the ADR process they were kind of experimenting. I was probably one of the first ones. They had a cross-examiner sitting there trying to make me out like I was telling a lie and I was trying to tell the truth. I got drunk the first time I ever told my story and I had been sober then for 5 years. I didn’t realize that’s when the whole idea of having support systems kind of started. I remember the shame of it, sitting in a bar. What happened to me? I was back to where I was. I’m drunk again. But I didn’t know what to do with the pain.

But I’ve told it so many times I’ve gotten stronger. I’m getting a little bit stronger. I can deal with the conflict now. I can deal with something upsetting in a more positive way and roll with it. Rather than reacting I can just roll with it. That’s a strength that I’ve learned through all of this and that’s what I want to teach kids, too. You don’t have to react all the time.

I guess the Elders used to tell me that as you get older you’ll learn to let go.

That’s all I have to say.

Q. Merci beaucoup.

— End of Interview

Êtes-vous un survivant des pensionnats?

Nous contacter pour partager votre histoire

Marie Tashoots

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Roy Dick

Pensionnat de Lower Post

Matilda Mallett

Pensionnat de Brandon

Evelyn Larivière

Pensionnat de Pine Creek et Pensionnat d'Assiniboia

Mabel Gray

Mission Saint-Bernard

Peggy Shannon Abraham

Alert Bay

Francis Bent

Pensionnat St. George's

Tim Antoine

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Ed Marten

Pensionnat Holy Angels

Terry Lusty

Pensionnat St. Joseph's

Kappo Philomène

Saint François Xavier

Janet Pâques

Pensionnat McKay

Lucille Mattess

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Rév. Mary Battaja

Pensionnat de Choutla

Grant Severight

Pensionnat St. Philips

Page Velma

Pensionnat indien de l'île Kuper

Corde Lorna

St.Paul's à Lebret, SK

Ambres de basilic

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Mabel Harry Fontaine

Pensionnat indien de Fort Alexander

Carole Dawson

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Walter West

Première nation de Takla

Elsie Paul

Pensionnat indien Sechelt

Joseph Desjarlais

Salle Lapointe, salle Breyant

Melvin Jack

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Aggie George

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dennis George Green

Pensionnat Ermineskin

Rita Watcheston

Lebret

Ed Bitternose

Pensionnat indien Gordon

Eunice Gray

Mission anglicane de St.Andrew

William McLean

Pensionnat de pierre, Poundmakers Pensionnat

Beverly Albrecht

Institut Mohawk

Harry McGillivray

Pensionnat indien de Prince Albert

Charles Scribe

École Jack River

Roy Nooski

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Robert Tomah

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Dillan Stonechild

Pensionnat indien de Qu'Appelle

Suamel Ross

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Arthur Fourstar

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Richard Kistabish

Pensionnat indien St.Marc's

George Francis

Pensionnat indien de l'île Shubenacadie

Verna Miller

Pensionnat indien de St. George's

Percy Ballantyne

Pensionnat indien de Birtle

Blanche Hill-Easton

Institut Mohawk

Brenda Bignell Arnault

Institut Mohawk

Riley Burns

Pensionnat de Gordons

Patricia Lewis

Pensionnat indien de Shubenacadie

Fleurs de Shirley

École Yale

Nazaire Azarie-Bird

Pensionnat indien St. Michael's

Julia Marks

École Christ King

Jennifer Wood

Pensionnat indien de Portage

David rayé loup

Pensionnat indien de St. Mary's

Johnny Brass

Pensionnat de Gordons

William George Lathlin

Pensionnat indien All Saints

Marie César

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Alfred Solonas

Pensionnat indien de Lejac

Darlène Laforme

Institut Mohawk

James Leon Sheldon

Pensionnat de Lower Point

Cecil Ketlo

Pensionnat indien de Lejac